Crytpo: There's just no legit use case for it. But, man, are these bros lobbied up.

Our looonnnggg take on why private digital currencies and the blockchain are an accident going out to happen.

[Hey, readers! This one goes on a bit, but my former CEA colleague, Ryan Cummings (who’s now at the Stanford Institute for Economic and Policy Research, where I’m a “Distinguished Policy Fellow”) and I had a lot to say about it. Much of this builds off a chapter we helped to write from the 2023 Economic Report of the President.]

Dan Davies and Henry Farrell have penned an important oped about the systemic risk embedded in digital currencies—the many stablecoins and cryptocurrencies out there—a risk that is significantly heightened by bipartisan Congressional support for legitimizing these non-sovereign assets. The authors explain how Congress’ blessing of these highly volatile currencies, particularly the normalization of stablecoins through the so-call GENIUS Act, could both undermine the role of dollar and create bail-out risk. Re the latter point, should they become a sizable part of the banking system, there’s a good chance that they’d end up being too-big-to-fail, and, should they crash, require tax-payer bailouts to stabilize the system.

But the oped does not say enough about the foundational problems with private digital currencies that should disqualify them from getting anywhere near the broader financial system. In this post, co-written with Ryan Cummings of the Stanford Institute for Economic and Policy Research, we go back a few steps prior to the current moment, and explain why, in our view, stablecoins and crypto are just fundamentally useless-at-best and harmful at worst. And, in agreement with Davies and Farrell, how the so-called GENIUS Act is a dangerous piece of legislation.

Unless you’re a criminal, there are no use cases for these currencies.

Crypto, and by extension, stablecoins, whose primary use is to buy and sell crypto, are, for reasons we explain, useless for normal commerce. Yet, they have two very prominent uses that have fostered their proliferation over the last decade-and-a-half. First, their anonymity makes them the currency-of-choice for scammers and thieves, and second, cryptocurrency speculators can trade them with each other and in so doing, quickly make—and lose—a lot of money.

The main reason for their lack of a legitimate use-case is the blockchain itself, the clunky, highly inefficient technology without which digital currencies would not exist. Blockchain technology requires any entity that wants to electronically record a transaction to spend time and money solving a complex math problem (“Proof of Work”) or put up collateral (“Proof of Stake”) in order to ensure that it’s costly to nefariously tamper with the database wherein the anonymized identities of the holders of these assets reside.

Buyer and sellers transact without knowing each other and without any centralized entity overseeing the whole process, making this a network that, in theory, is resistant to tampering, censorship, and can keep all records over all of time in one place.

But there’s a problem, not just for crypto, but for any legit application of blockchain technology. In the existing world of traditional finance, or home loans or title insurance, or whatever, the identity of the other party is the singular most important piece of information. Imagine, for example, that you’re trying to buy a stock on Robinhood. To perform this transaction, Robinhood needs to know both your identity (where the money is coming from), and the identity of the market-maker selling you the stock (where your money is going). If both are completely anonymous to Robinhood, they don’t know if you are a legit retail trader trying to buy or sell a stock, a thief who is using stolen funds, or a criminal with ties to a terrorist organization.

This problem can be ameliorated through blockchain technology by creating a “permissioned” network, where a “trusted” entity approves participants on the network, who all have their identity tied their network activity. But besides needlessly recreating the existing pre-crypto, sovereign system, to do so would create a private network with all the costs associated with operating a blockchain and few, if any, of the benefits—certainly not anonymity and a lack of centralization. And this is much less efficient than existing database systems.

To give a sense of the scale of the inefficiency, analysis we did in the Biden administration gave an example of Walmart’s blockchain usage that was up to 50 million times (not a typo) less efficient, in terms of compute, than a traditional database configuration. A strong hint about the blockchain’s inefficiency comes from the revealed preferences of large tech firms. With all their computer scientists and trillions of dollars, none of them use it. Even the crypto exchanges themselves are not using blockchain technology to settle trades!

One of crypto’s more appealing promises—to provide a means for individuals in developing countries to have access to a payment asset beyond the control of their government—falls short. Zeke Faux, in his great book on the crypto industry, Number Go Up, tried in various places around the globe to use a cryptocurrency to buy things, only to default to his Visa card, which was invariably cheaper and faster.

While crypto’s huge computational costs undermine any legitimate use case, the benefits of anonymity and the lack of a centralized authority are well worth the inefficiencies in one particular context: if you want to transfer money to commit crimes. For example, crypto is an increasingly popular way of moving funds by drug cartels in Latin and Southern America. Indeed, the firm Chainalysis estimates that in the past three years roughly $140 billion of cryptocurrency was used for illegal activity.

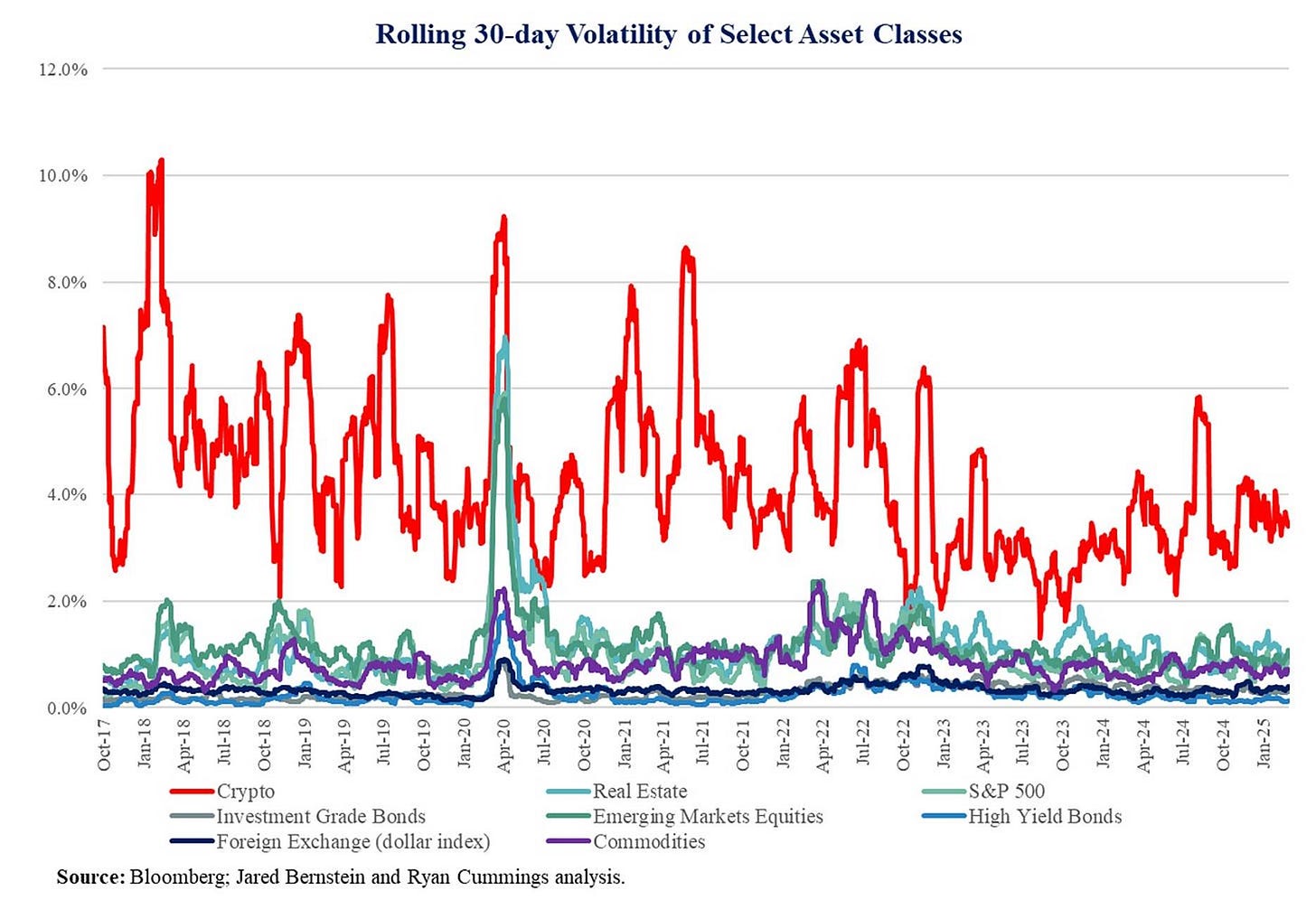

Another factor undermining their use is their volatility. For money to be useful, it has to be a reliable store of value, but crypto’s volatility, as shown in the figure below, disqualifies it from utility in commerce.

In other words, these currencies contribute nothing at all to commerce--the buying and selling that moves the economy forward as we pursue our wants and needs. As CEA wrote in the 2023 Economic Report of the President, “crypto assets to date do not appear to offer investments with any fundamental value, nor do they act as an effective alternative to fiat money, improve financial inclusion, or make payments more efficient; instead, their innovation has been mostly about creating artificial scarcity in order to support crypto assets’ prices—and many of them have no fundamental value.” Or put differently, we like to (half) joke that the true, fundamental value of cryptocurrencies is that they can be exchanged for U.S. dollars, which can then be used to buy goods and services.

If crypto disappeared tomorrow, the average person going about their economic life wouldn’t even notice. But the crypto bros would notice, and so would the politicians whose pockets they so lavishly line.

Why then, do these currencies not just exist, but have proliferated and appreciated!?

Fair question. One answer is, as noted, that they are currency of criminality.

But it’s also true that fortunes can be quickly made or lost by trading or facilitating trading these currencies. It is this characteristic, leavened with lavish campaign contributions, that eventually captured the interest of President Trump, whose huckster instincts quickly recognized that his followers would be happy to buy and trade coins with which he’s associated, on a platform that his family owns, providing him with a skimming operation that’s yielded him and his family billions.

But, of course, the crypto phenomenon goes way beyond Trump. There are a lot of risk-seekers who like to place bets in this casino, and that demand helps to explain its proliferation and appreciation. Strong demand + artificial scarcity = price appreciation.

And if that’s your thing, so be it. Whether it’s buying and selling electronic trading cards, often featuring digital images of deformed apes, or just trying to get rich quick in an extremely volatile market, the venerable principle of consumer sovereignty—people ought to be able to trade what they want, assuming common sense guardrails that protect the rest of us from their actions—suggests that the people who really like this stuff ought to be able to play with it.

But there is a much more powerful and much less benign force for crypto’s durability, one that one of us (Bernstein) got to experience firsthand: the industry has lobbied-up faster than any we’ve seen. When I was making the rounds in the Senate prior to my confirmation hearing to be Chair of the Council of Economic Advisers, I sat down with Senator Lummis’ staff, ready to go through all the important economic issues I’d be overseeing: jobs, growth, inflation, budgets. But all they wanted to hear was that I wasn’t interested in going after the digital services industry. She opposed me, so I guess my nuanced answer—some version of “it’s not going away but we need to keep it from whacking both the people who don’t understand it and the broader economy”-- did not appease.

But recognizing that we must live with this destructive asset doesn’t mean we have to elevate it. Under our watch, we argued not to banish crypto, but essentially keep it in a sandbox so enthusiasts can play with it without fraud, speculation, or scams hurting bystanders. But the industry’s lobbyists brought a bazooka to a knife fight this election cycle, accounting for roughly half of all corporate spending in the 2024 election (and an amount that converted Trump from a skeptic to a huge booster). And this investment is paying off, having bored so deeply into the current Administration and Congress that they’ve successfully removed guardrails and written custom legislation to protect the industry from regulatory scrutiny. They’re now inside the (White)house, supporting broad integration of the traditional financial system and the volatility and madness that occurs within the crypto ecosystem.

The GENIUS Act

Which brings us to the GENIUS Act (Guiding and Establishing National Innovation for U.S. Stablecoins Act), the one Davies and Farrell properly warn us about and is currently under debate (it advanced in the Senate, 66-32). In a nutshell, this bill, instead of productively ring-fencing crypto into its own playground, does the exact opposite: it gives crypto a direct line into the arteries of the financial system, making it arguably the single most dangerous threat to financial stability since the Great Financial Crisis of 2007-2008.

More specifically, the bill attempts to give a regulatory stamp of approval to a particular crypto product referred to as a “stablecoin.” Stablecoins are issued by private firms who claim that for every stablecoin issued, there is exactly $1 backing the token. That is, one unit of Tether—the most popular stablecoin—is always supposed to be worth $1. Stablecoin issuers promise they’re good for their money by claiming (an assertion they currently don’t have to document or prove) to have abundant reserves backing up the issued coins, so if stablecoin holders want their money back, at any time, the issuer can provide the dollars by simply buying back the coins from their alleged dollar reserves.

Economists think about stablecoins as having not only zero, but negative economic value. To understand why, consider if you had $1 and were debating between parking it in a savings account and a stablecoin. You would never rationally choose to put it in the stablecoin for two reasons. First, stablecoins pay no interest, unlike a typical savings account. Second, and more important, is that when you deposit money in a bank account that has below $250,000, every cent is guaranteed by FDIC deposit insurance. With stablecoins, there is no such guarantee by the government, and you are wholly exposed to the credit risk of the issuer. As former Senior Adviser to former SEC Chairman Gary Gensler Amanda Fischer likes to say “if you hate earning money and love credit risk, have I got a product for you.”

So why do people hold stablecoins? Because they provide speculators with a dollar-linked “on-ramp” into and “off-ramp” out of cryptocurrencies. That is, when speculators want to take dollars and buy cryptocurrencies, they typically first buy stablecoins, as this is 1) easier to get money from a bank to a stablecoin issuer than it is from a bank to more exotic cryptocurrencies, 2) crypto exchanges display the value of particular tokens relative to stablecoins, not to the dollars that are allegedly underlying them, and 3) stablecoins do earn interest on crypto exchanges (which is paid in other cryptocurrencies). Likewise, to get your money out of crypto, speculators typically first sell their tokens for stablecoins, and then redeem the stablecoins for dollars. A natural analogy to draw here is that stablecoins are poker chips in a casino: they’re an intermediate vehicle which makes gambling a little easier. Indeed, Gary Gensler made this exact comparison back in 2021.

Enter the GENIUS Act. The bill attempts to provide the regulatory imprimatur for stablecoins through two primary mechanisms. First, it allows big banks to create subsidiaries that can issue stablecoins, connecting large banks to the crypto trade. For stablecoin issuers under $10 billion in total tokens outstanding, the bill is a dream come true, as it allows them to engage in jurisdictional shopping and register with states like Wyoming (Sen. Loomis’ state) that have extremely limited regulation and oversight of crypto products.

Second, and more concerning to us, is the bill’s attempt to treat stablecoins like traditional bank deposits. That is, the bill permits stablecoins issued by a registered entity to be treated from a regulatory perspective just like a dollar is for payment and settlement purposes. Like Davies and Farrell, we fear this invokes run-risk, largely because while dollar deposits (under $250,000) are insured, “the Genius Act’s drafters…have no clear response to a critical question: Does the United States stand behind dollar-based stablecoins or not?” In other words, the minute an established bank with significant stablecoin holdings gets into any sort of trouble, stablecoin holders will want dollars, forcing the bank into a fire sale of the short-dated bills it holds to back the coins.

And this is a movie we’ve seen too many times. The next step is a government bail out with taxpayers left holding the bag. In this way, the GENIUS Act links the U.S. taxpayer to a highly volatile, non-sovereign currency. If that’s genius, we’d hate to see what the idiots are up to.

Conclusion: What’s really going on here?

In 1977, the late economist Hyman Minsky laid out a framework for how financial crises begin in what is now commonly called a “Minsky cycle.” According to Minsky, the birth of a financial crisis begins in the ashes of the one that came before it. That is, after a financial crisis, memories of excessive speculation generating systemic risk to the system are fresh and as a result lending standards are strict. Then, as the crisis lingers less, speculation gets more aggressive and “innovative” (i.e., opaque), and projects that require continuous, rolling-debt financing begin to proliferate. Finally, once the crisis is a distant memory, “Ponzi finance” emerges, where new debt is issued to cover old debt. The inherent fragility of Ponzi finance schemes invariably unwind, creating a new crisis and a sudden, brutal deleveraging.

The GENIUS Act is morbidly innovative in the sense that it skips the first two steps of a Minsky cycle and jumps straight to the third—Ponzi finance. The bill sets the stage for an entire class of speculative assets that have precisely zero underlying cash flows to be integrated into the financial system. All for the purposes of satisfying an industry whose main contribution to most Americans has been scamming them.

This leaves us with the fact that the crypto lobby and the politicians they control—in both parties, to be clear—are are setting the table for the next financial crisis, aided by a President engaged in a massive grift, selling digital meme coins and ramping up his family’s own crypto exchange. If this mess was portrayed in an HBO series, you wouldn’t believe it. And we haven’t even raised the specter of Strategic Bitcoin Reserve, another boneheaded idea whose only possible purpose could be to pump up the value of the President’s favored coins.

That’s what’s going on here: a timebomb is being set by at the behest of a privileged few who want to squeeze every cent they can out of future-bag holders. What’s not going on is the pursuit of policies that might actually help the working-class voters who helped elect this administration. Instead, they’re getting sweeping tariffs that will make their lives more expensive and an appalling budget-busting set of tax cuts for the wealthy whose cost is very partially offset though cuts to health care and nutritional benefits of the poor.

And when that bomb detonates, who do you think will be called upon to clean up the mess?

Could we stop being stupid?

Call these Democratic senators who favors the bill and just say “No.”

Ruben Gallego (D-AZ), Mark Warner (D-VA), Lisa Blunt Rochester (D-PA), Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY), and Angela Alsobrooks (D-MD)

Excellent post explaining in detail the problems of cryptocurrency. My first reaction is frustration because when the Ponzi scheme fails, I and millions of people who oppose this scheme will be forced against our will to bail out the people who profited from cryptocurrency. There is no way cryptocurrency should be integrated into our currency system.