Housing (Un)affordability: New Reports Shed New Light on the Problem

I'm especially convinced that with better policy, we could improve our uniquely dismal construction productivity.

The difficulty that people young and old are experiencing when it comes to housing is at the heart of the ongoing affordability crisis. In far too many parts of the country, far too many young families are unable to grasp onto the lowest rung of the housing market. Part of the reason for this lack of churn—a critical, missing dynamic in today’s housing market—is that older, established homeowners who’d like to move are locked into their residences by a mortgage rate that’s much lower than the spot rate on the current market.

But another reason—one that speaks loudly to affordability concerns—is that too many renters are paying so much of their income for rent, they can’t afford to save for a house. To be clear, I don’t mean to enshrine home ownership as a sacred goal. I happily rented well into adulthood. It was nice to be able to tell my landlord to repair something and have him ignore it, just like I do now in my own house. But when you’re paying 50% of your income on rent, let’s face it: your economic life is off to very tough start.

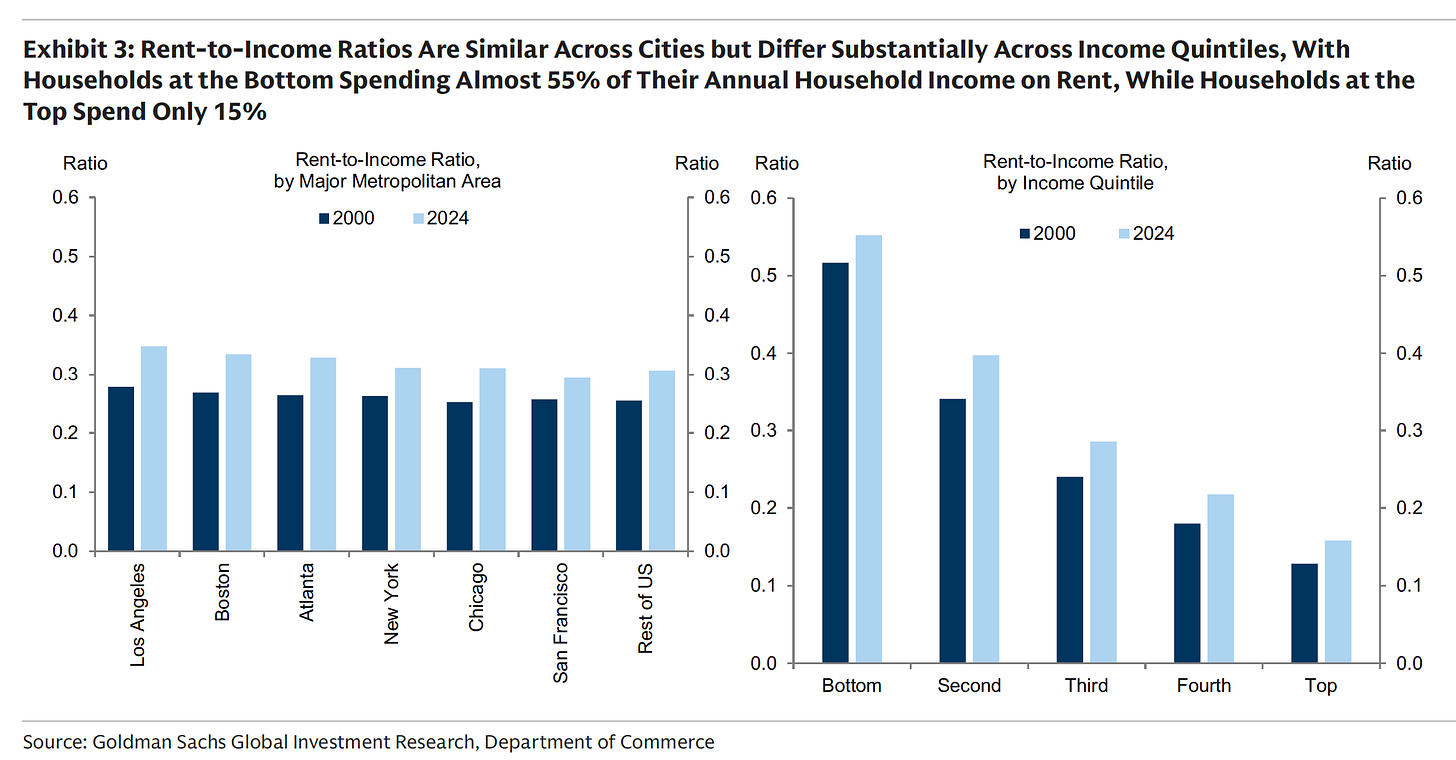

As the very sharp Elsie Peng points out in a new piece from GS Research (paywalled), rent/income ratios are up from 2020, are pretty similar across geographies, and are much higher at the low end. That’s long been the case, but it’s gotten worse:

For renters, housing costs are high by historical standards. Rent currently amounts to 32% of the average renter’s household income, somewhat above the 27% share in 2000. But it amounts to 55% of income for the bottom quintile and 40% for the second lowest quintile, each roughly 5pp higher than in 2000.

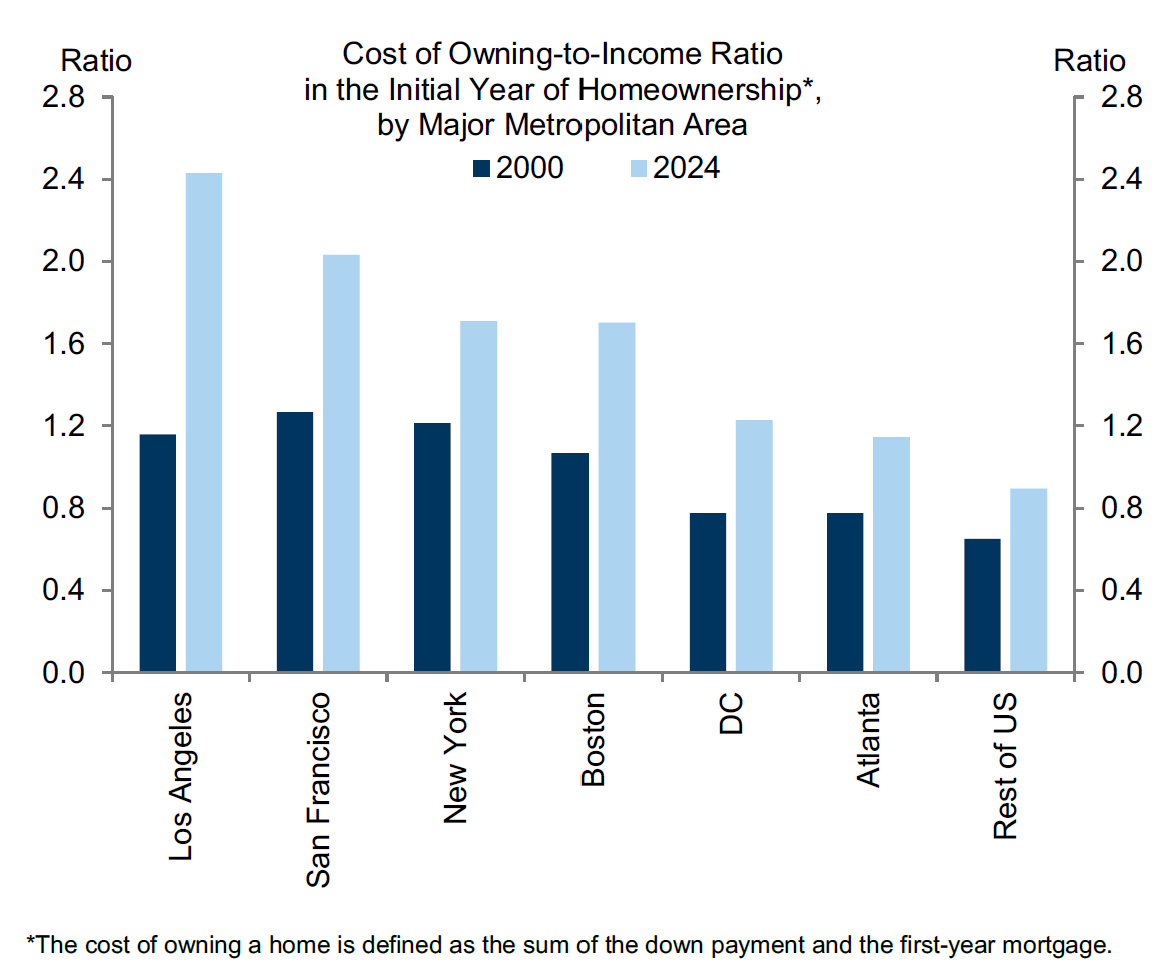

It’s even tougher for those aspiring to homeownership: “For young married couples considering buying their first home, the average down payment is now 70% of their annual household income (vs. 58% in 2019 and 45% in 2000) and the first-year mortgage payment is about 25% (vs. 18% in 2019 and 20% in 2000).”

And the sum of down-payment and first-year mortgage payments relative to incomes has shot up in major metro areas.

Peng then gets to the heart of the affordability debate, which some analysts want to dismiss (as does Trump on alternate days) as just the usual variation in prices. Their argument is that some prices will always rise faster than average while others rise slower than average. That’s just life, and it’s arbitrary to isolate the prices rising faster than average and call that a crisis.

Over to Peng:

If consumers’ overall spending power grows at a normal pace, should we still worry about a particular item being more expensive than usual? We think the answer is yes in the case of housing, especially owner-occupied housing, because it is different in two crucial respects.

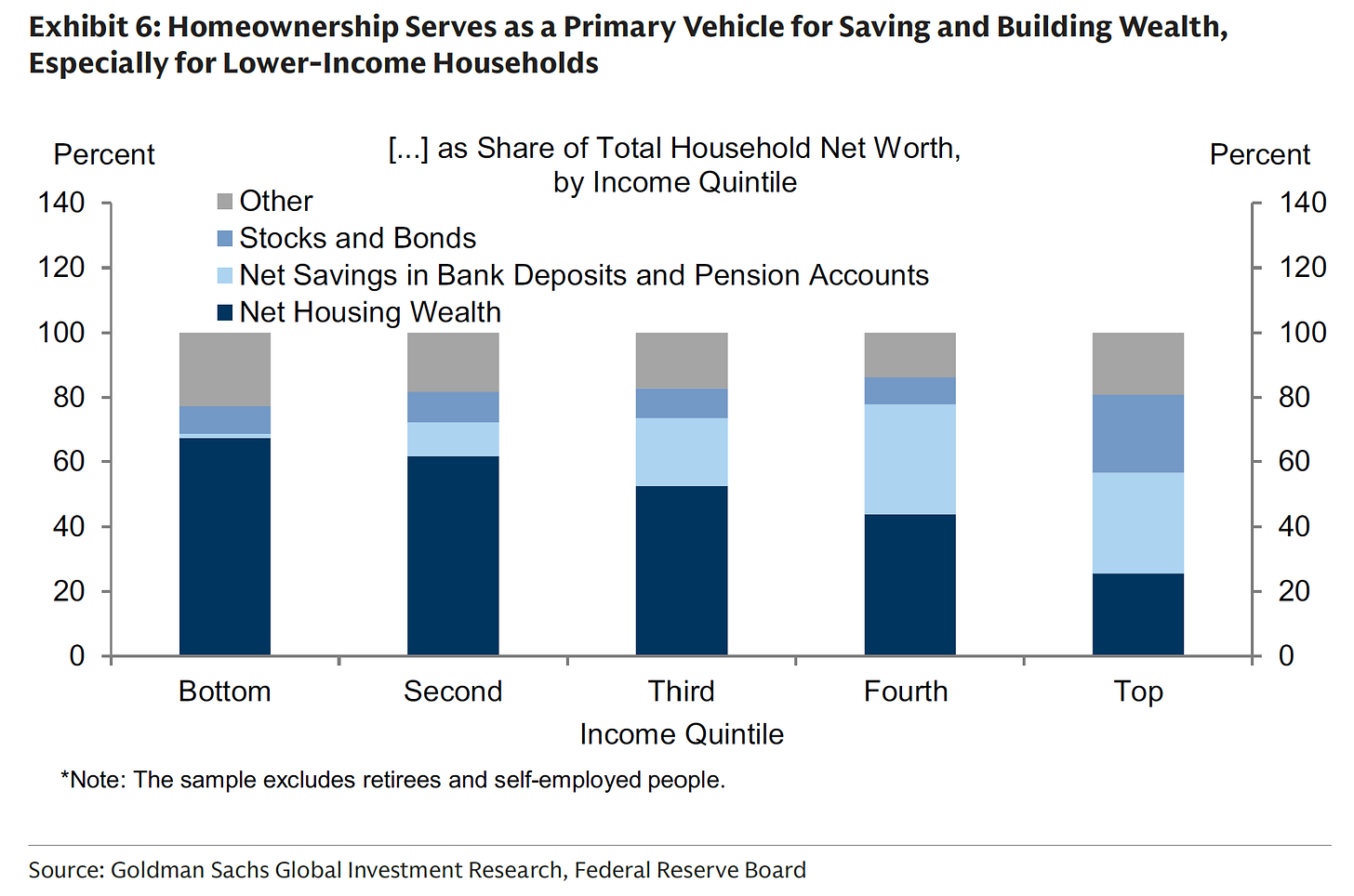

First, owner-occupied housing is the primary way that many households, especially low-income households, save and build wealth. [The figure below] shows that real estate assets account for nearly 70% of the net worth of households in the bottom income quintile but only 20% for households in the top.

I’d add that this channel of wealth formation is especially valuable for families of color.

The second reason Peng stresses why housing affordability is so consequential is that, as anyone who’s ever shopped in this market knows, home prices strongly correlate with the quality of public schools.

As a result, for many households, the unaffordability of owner-occupied housing is more than just a cost of living problem. It also means higher barriers to building wealth and more limited access to education services, job opportunities in large and growing cities, and long-term social mobility.

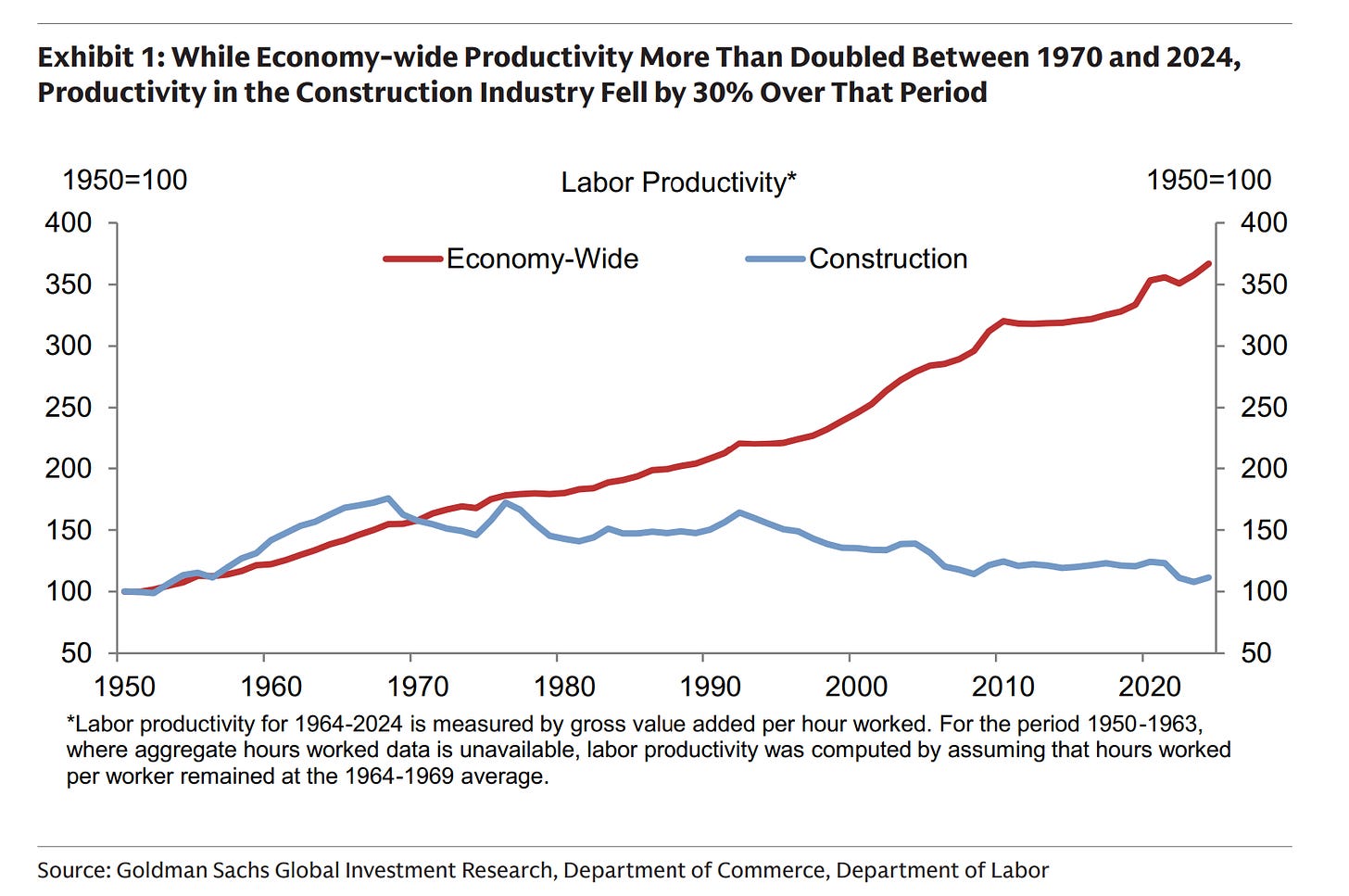

Now, for the second punch from this knockout combo, I and everyone else in the housing space, including the Abundance folks, have argued that land-use restrictions are one of the reasons why building is too expensive in many parts of the country, a fact that impinges on both rental and single-family home construction. What I haven’t done is tie this to a key constraint in housing affordability, a real anchor around the neck of the problem: the terrible record of productivity in the construction sector, both in absolute terms and relative to other industries, and even to other countries (construction productivity has lagged in most countries, but it’s worse here).

Now, there’s a lot that goes into that gap, including lack of technological innovation and the fact that if you go by a construction site, it may not be exactly just a bunch of hammers and nails at work but, again citing GS Research, “most of the major machines used for construction today had already been invented in the 1950s.”

But it’s also the case that the increase in land-use restrictions, NIMBYism, lot-size and height restrictions, permitting hassles and barriers, and so on have “been a major drag on construction productivity growth.” In recent years, looking both at the US and other advanced economies, “changes in land use regulations explain most of the difference in construction productivity growth between US and other G10 countries.”

What are the mechanisms by which this occurs? For one, just raising the cost of production lowers the value of real output which is the numerator in productivity (output/hour). For another, jamming the process with inefficiencies and barriers to entry whack price-reducing competition.

Rules that restrict the size and height of new buildings also weigh on construction productivity growth, likely because they lead to inefficient investment decisions across different locations. State political involvement, local approval requirements, and impact fees can also lower construction productivity growth, by raising barriers for new developers to enter, thereby reducing local competition.

The fact that much of this regulatory sludge is decided at the local level, and that there are something like 20,000 such jurisdictions across the land, make this a daunting political problem. But it is amenable to policy, which was the starting point for our CAP policy proposals herein, including using the leverage of federal carrots and sticks to push localities to do the right thing (we also stress policy changes that would give modular and manufactured housing a better chance to grow, and this too would help with productivity growth).

What this new research shows is that the housing affordability shortfall is real, it’s important, especially when we consider the share of income many renters are paying and the opportunity costs to wealth accumulation of not being able to own a home. Moreover, that construction productivity chart above is just screaming for a solution, and the research is clear and persuasive that loosening land-use restrictions, as tough as that is to do, is a big part of that solution.

In many rural tourist areas in the West the issue most affecting housing availability is AirBnB, VRBO, etc. Why would an owner rent a property at $1500/month to a local when they could get $3500-$7000/month renting it to tourists? In some places like Sedona, Flagstaff, Prescott all in Arizona a large percentage of the housing is used for short term rentals. The city of Sedona has been asking the State to allow it to limit the number of short term rentals so they can increase the available housing for local workers. In Aspen/Snowmass it was the Hollywood crowd that bought much of the houses, which then sit vacant for most of the year, only to be used by the owners during peak ski season. Aspen/Snowmass in Colorado dealt with their housing crisis by designating certain housing units for local workers with rents and purchase prices limited to rising only with general inflation. They also have a lottery to determine who among interested buyers or renters gets a property, and to qualify the person must be a local who has worked in Aspen for at least 1 year before they can sign up for a lottery. There is very little available land to build in these narrow valleys. In cities such as Phoenix and L.A. the prices of houses and rentals are the big issue, wages simply haven’t kept up. Investors buy properties and jack up the prices, willing to sit on unsold units until the market comes to them. In Arizona cities water is now a big constraint on development. Some developments are built without water access and then sold to uneducated buyers who truck in water thinking that the cities will extend water to them eventually. But there are limits in a climate-change drying desert as to how much water can go to places. Right now we also have data centers that are sucking up water (and electricity which drives up rates) that could go to homes. Another area using water are almond and other nut farms, for all of the alternative milk products that are so popular. And alfalfa farms that ship overseas are driving up prices of feed for livestock owners and also using up 10,000 year old aquifers that houses in those rural areas depend on. The water is literally being exported in the alfalfa that goes to China or Saudi Arabia. Without water it’s hard to build houses in the desert. If a well goes dry a house can lose half of its value instantly. In addition individuals wanting to build their own homes are finding it very expensive (I know as I have done this) a single family home in my region costs between $400-$600 per square foot to build, that’s not including the land. And the trades have just been attacked by ICE. Nearly every roofing employee in the southwest is undocumented. Who wants to work in the sun in 115 degree temps during the exceedingly long hot summers here? Skilled trades people are hard to find and have jacked their rates up because of demand. In some cases building a home can take over two years because you are waiting on good tradespeople. The tariffs have affected prices too, a well that in 2017 would cost $17k to drill now costs over $60k because of materials costs. So there are plenty of other reasons besides zoning restrictions and regulations on building safe affordable housing that make it hard to build.

Not all land use restrictions are the same, nor may all fall on the same side of the ledger. Restrictions on sprawl, where that sprawl causes serious ecological damage, can be positive in the long term. Consider the destruction of wetlands. Wetlands buffer the flooding that can wipe out housing.