Tariff Passthrough to Prices: Where Is It?

It's definitely there, but so far less than one might have expected.

There’s this myth that Republicans are anti-tax. Many have signed pledges never to raise taxes. Yet, they’ve been fully complicit in Trump’s major tax increase when it comes to import taxes, aka tariffs. Such taxes, as the Budget Lab has shown, are regressive, because imports comprise a bigger market-basket share for lower income households.

Of course, this analysis (correctly) assumes some degree of consumer passthrough (pt) from importers who directly pay the tariffs (contrary to Trumpian nonsense about exporters “eating the tariffs”—if that were so, Customs wouldn’t have collected a record $28 billion from importers last month) to wholesalers, retailers and so on down the chain to its last link: the consumer.

Because the national price indices haven’t reflected much pt yet, questions regarding our incidence assumptions (who ultimately pays the tax) have arisen. Empirical evidence leads economists to expect high consumer pt, in the range of 80-100 percent, which we haven’t yet seen in this trade war. Why not, and what should we expect going forward?

Here are some answers to those questions, taken from a smart new analysis from Elsie Peng of the Goldman Sachs research team (behind paywall), Neale Mahoney (past and future Let’s Do Lunch guest, Stanford prof, director of SIEPR), and my personal noodle.

—First and most important, consumer pt has occurred, as I show below.

—It takes time for the tariffs to work their way down the chain. I know it feels like we’ve been at this for years, but this trade war started in April!

—As I’ve noted before, firms front-ran the tariffs by aggressively stocking their inventories with pre-tariffed-priced goods.

—Exporters have been absorbing some of the tariffs; based on import-price analysis, Peng puts that at 20% so far.

—Profit margins expanded during the pandemic as many firms raised prices more than necessary to offset the higher costs of their inputs. Therefore they can, for a time, cut into these margins to avoid full pt.

—Consumers are highly price sensitive these days, and that means firms that raise prices risk losing sales. Neale cites newly resumed student loan payments and the fading of post-pandemic excess savings as factors in play here.

—Overall consumer demand is weaker than you might think. I’m referring to the finding I’ve touted here that real consumer spending is up 0% this year (Dec-May)!

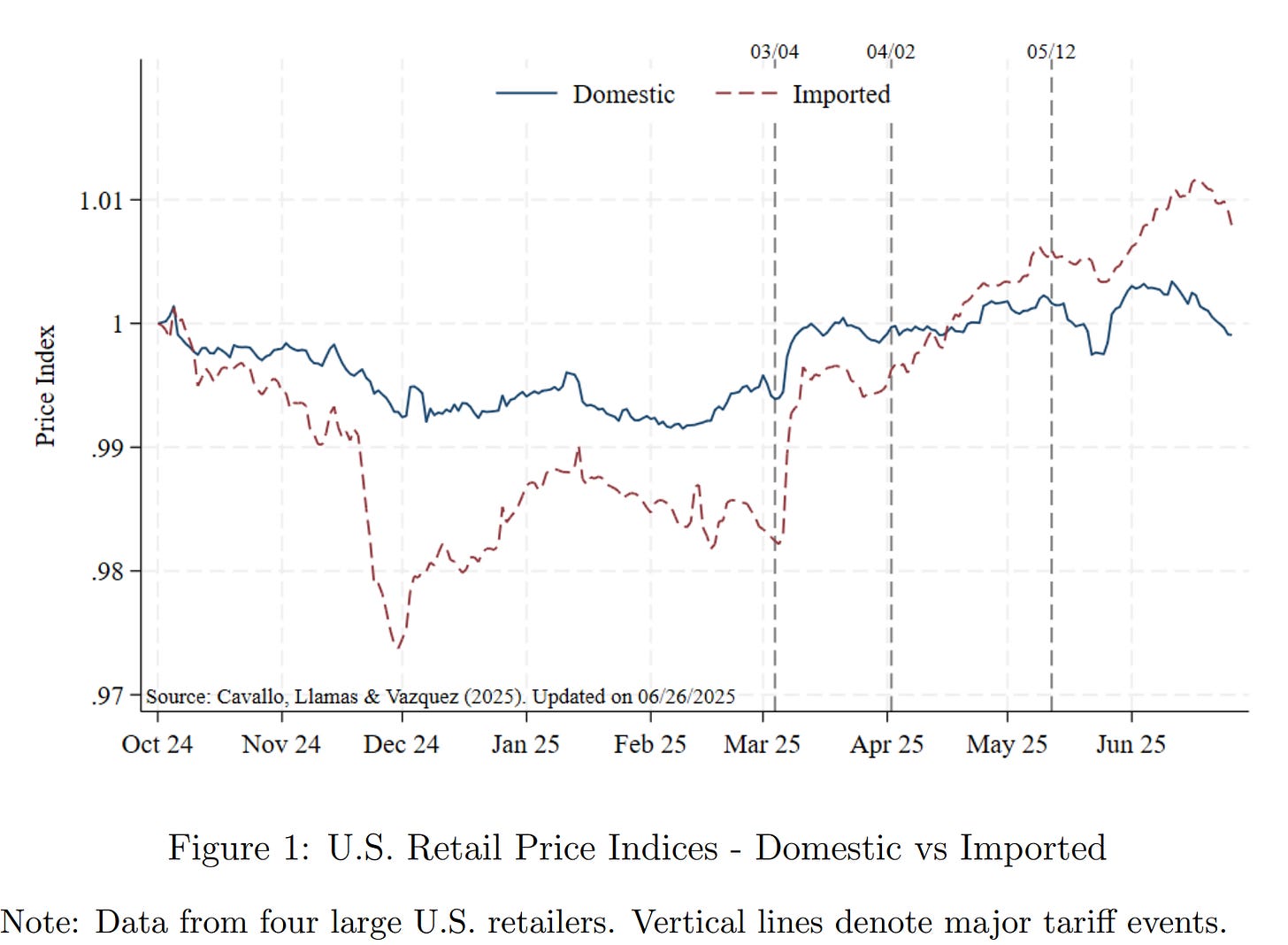

One place you see pt is in some recent innovative work by Cavallo et al. These researchers built a database capturing prices from large domestic retailers, with information on product country-of-origin. As I wrote yesterday:

The database shows clear, though not yet large, price increases in imported goods; the researchers conclude that “the announcement of U.S. tariffs prompted rapid but still relatively modest price adjustments” and “increases for Chinese goods were both larger and more persistent” than those from other exporters.

Here’s a picture from their work, showing notable jumps in imported goods’ prices around tariff announcements:

Pre-trade war, imported goods inflation lagged domestic; now it’s ahead.

Another e.g. of pt, one I’d thought I’d seen in recent inflation prints but Ernie T clarified (because that’s what he does), is goods inflation providing less disinflationary support. Here’s Ernie’s graphic on this:

The Peng study I noted is the most detailed to date on pt. Here’s the key ‘graf and the key graph; she estimates that so far, 40% of the higher tariffs have been pt’ed to consumers, well below the 70% at this point in Trump’s last trade war:

We have assumed, based mainly on our analysis of the last trade war, that 70% of the direct costs of tariffs would fall on consumers, and that the total would rise to about 100% when combined with spillover effects to prices charged by domestic producers who benefit from protection from foreign competition. Since it is still early for spillover effects to appear, our 40% estimate above is most comparable at this point to the 70% direct effect.

Note, importantly, that Peng and the GS team expect a) pt to peak at 50-60%, and b) core PCE inflation to be 1 percentage point higher this year due to the tariffs: 3.3% instead of 2.3%. That’s not nothing, and reflects recent Trumpian escalation. If they’re right, it certainly supports Fed Chair Powell’s staying in wait-and-see mode for now.

Bottom line, there’s just a strong gravitational pull for the cost of tariffs to be passed through to consumers. No one can know what to make of Trump’s recent musings re much higher tariffs kicking in on Aug 1 (I doubt it), 200% on pharmaceuticals (not gonna happen), 50% on copper (maybe; the sectoral tariff threats tend to be a bit more likely), but go back to the list above of factors dampening pt. The inventory and profit margin constraints will fade, and my guess is that’s enough to take pt higher than Peng’s 60%, but we’ll see.

Oh, and I guess I shouldn’t forget to mention: all of this is terrible, unnecessary, damaging economics. Just one own-goal kick after another. And why? Because the president has a deeply embedded misguided understanding of the costs and benefits of global trade and none of his lackeys dare to correct him.

None of his lackeys have the professional training needed to correct him.

Why does the press not correct Trump that it is American consumers that pay the tariffs, not the countries themselves, as Lawrence O'Donnell commonly talks about?