Ryan and I have an oped in today’s NYT arguing that investment in AI looks awfully bubbly. Such a call must be speculative, as it’s made on our judgement of the gap between a known—current valuations of the technology and the firms that are developing it—and an unknown: whether future returns will justify what looks frothy to us.

To be clear, we’re far from alone in this call; there’s knowledgeable folks on both sides. No one can rule out the possibility that AI could eventually—timing matters in bubbles—truly transform production, innovation, and productivity growth. In fact, one of our more important points is that investment in a technology can both inflate a bubble and that underlying asset can turn out to be transformational. See railroads (bubble in the 1870s) and the internet (bubble in the late 1990s).

But we’re here today to go a bit deeper into some of the points we didn’t have space to fully develop.

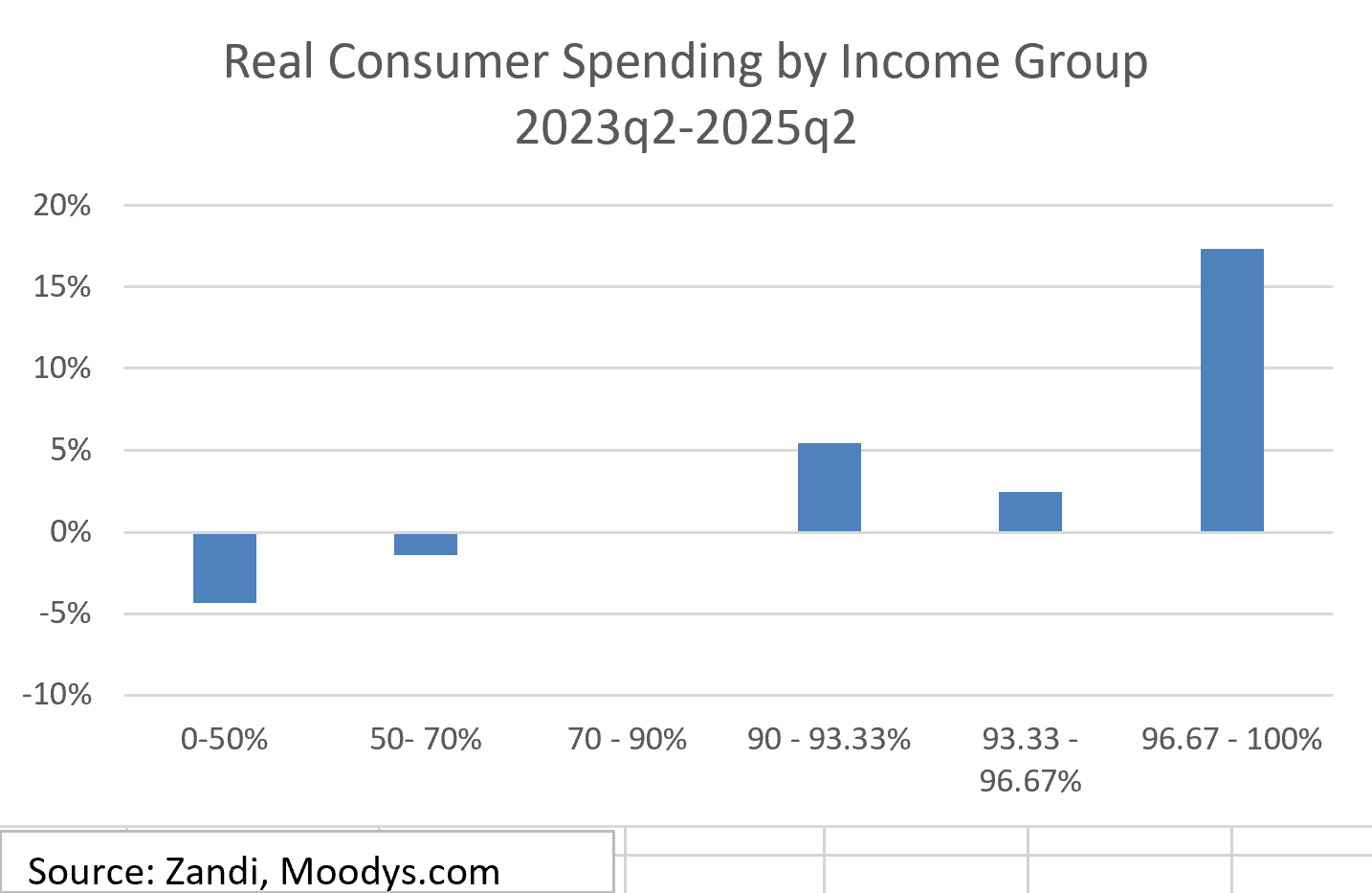

The Wealth Effect: A Real Vulnerability

As we allude to in the oped, if we’re right and the AI bubble should burst, the timing is inopportune in a specific way regarding the wealth effect, which one recent estimate puts at just under 3 cents on the dollar (one dollar of added stock market wealth adds 2.8 cents to consumer spending). In the piece, we cite Mark Zandi’s consumer spending by income class, but here are the data, showing real changes over the past two years (and here’s a great Zandi piece on these wealth effect dynamics).

These data, which Mark and team derive by disaggregating the spending data in the macro accounts using distributional information from the Fed’s Survey of Consumer Finances, suggest real spending growth has been flat for most consumers, but booming at the top. Again, the distribution is imputed, and I wouldn’t swear by the exact numbers, but the pattern certainly squares with the vibes. And, as we stress, those folks at the top contributing most to current spending growth are by far the biggest shareholders. Say, just to make this more concrete, that the $20.4 trillion Mag 7 market cap tanks by a third. That’s about $190 billion lost spending through the wealth effect, over half-a-point of GDP.

But What About The Earnings?

In a thoughtful op-ed that points in the opposite direction of our piece, Nir Kaissar at Bloomberg argues that the comparison to the dot-com bubble is off because firms in the Mag 7 have had strong earnings (profits) in the recent past. Moreover, the return on equity (another common measure of profitability) of the Mag 7 last year was a stunning 68%, more than double the top 8 firms at the height of the dot-com bubble.

While we agree that the firms today are much more profitable than the speculative businesses of the dot-com bubble, an important distinction needs to be made: the Mag 7, with the exception of NVIDIA, is receiving almost all of their earnings growth not from AI, though that’s where the bubbly investments we document are being made. As we wrote: “a bubble occurs when the level of investment in an asset becomes persistently detached from the amount of profit that asset could plausibly generate.” That asset is AI, not other stuff.

Take Microsoft, for example. In an earnings call earlier this year, they noted that Azure AI services contributed 13 percentage points to Azure’s (their cloud platform) overall annual growth. Not bad by any means, but a tiny fraction of the 157% overall annual growth that Azure had. Amazon’s CEO likewise noted in a conference call last year that revenue from AI could be expected to generate “tens of billions of dollars of revenue over the next several years,” but noted that in the context of their business—which does hundreds of billions in revenue each year—this is a tiny share.

Put another way, firms like Microsoft, Amazon, Google, and Meta are drawing large profits from selling ads, cloud services, and, well, anything you can buy on Amazon. And they’re using these profits to make huge investments in AI; these four firms combined are planning to spend $335 billion in capex this year alone. But a tiny portion of their earnings are coming directly from those massive AI investments. And that’s why we think it’s more likely than not that we’re in a bubble—if all of the massive investments in AI only help firms become marginally more productive in the short run, then these huge expenditures will not generate enough profits to have justified the large investments.

A Thought On How We’re In A Bubble.

The stock market can broadly be viewed as a (mostly) efficient, ruthless information processing machine. But as we argue in our piece, the machine can sometimes break down. We didn’t have the room in the piece though to talk about how we got into the bubble.

Bubbles are common throughout history and happen for different reasons. For example, in a seminal paper from 1990, U.C. Berkeley’s Brad De Long and others argue that irrational traders (such as those using YOLO strategies) can make it prohibitively expensive to bet against a downfall because, as Keynes says, the market can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent. But the share of retail activity relative to institutional traders may be too small in the AI case to drive a large and permanent divergence.

Investors could also be exhibiting herd behavior. In a canonical paper from 1992, Nobel laureate Abhijib Banerjee laid out a simple model where even rational individuals can create an inefficient equilibrium like a bubble.[1] In essence, the model shows that even if an individual has good information about how to make a decision, they might still follow the choices of others because they believe the others have better information. The stock market does some of this mechanically; increasing valuations increase the market cap of firms, which then increases their weight in an index, which ultimately causes more shares to be bought by passive investors that are tracking the index. But it’s also the case that investors are listening to each other and acting accordingly, i.e., they’re herding.

But perhaps the best academic explanation of the cause of the current bubble is from Pástor and Veronesi (2009). They show that if a new technology (such as AI) is being adopted quickly, it can be rational to put large amounts of investment into the technology, even if the ultimate value is uncertain. This is because it can take time to learn about the ultimate profitability of a technology, and, should the technology be a success, investing too late will result in large lost gains. Or in other words, even if a technology is revolutionary, it’s just too hard to predict when that will happen and to whom. So, you gotta speculate!

Bottom line, you can’t be sure it’s a bubble until it pops. Neither are we saying much here about the big AI questions, like its impact on jobs for humans, its productivity impacts, how it affects our culture, electricity costs, the environment, and on and on. Our observations are more narrow, just focusing on the financing, which looks more bubbly than not. Given that the underlying economy and the things we care most about—jobs, wages, incomes, affordability—are already showing some fragilities, it’s important to carefully monitor this potential bubble. We’ve got enough to worry about without adding a big, negative wealth effect to the mix.

[1] Interestingly, Banerjee would win the Nobel for his work on randomized control trials and development economics.

I think you meant "allude to" rather than "elude to" in the fourth paragraph.

AIG’s credit default swaps ended up

bringing down counterparties that were all interconnected. If / when the AI bubble bursts- what kind of ripple effect can you imagine?

When Wall Street got sick - they got bailed out . When Main Street got clobbered - “ better luck next time “.