What do we mean when we say government debt is "unsustainable?"

The word has been an abstraction. Incompetent leadership is changing that.

By all accounts, from the left to the right, the Republican budget they’re struggling to pass will add trillions to the nation’s debt. The always astute Jessica Reidl, budget analyst from the conservative Manhattan Institute stated that, "This tax bill's enormity is being underplayed. This tax bill will cost more than the 2017 tax cuts, the CARES Act, Biden's stimulus, and the Inflation Reduction Act combined. It would add $6 trillion over 10 years to the deficit."

I myself, and this was before this awful tax bill was in the mix (“awful” here refers more to its hyper-aggressive, reverse-Robin-Hood structure; Republican tax writers clearly looked out upon the firmament and resolved that the poor have too much and the rich, not enough), often defined our fiscal path as “unsustainable.”

I think that’s true, but I also think it’s not been a particularly helpful word. What is it that is not being sustained, and why, if folks have been saying this for awhile, has nothing exploded? If I’m running my car engine at an unsustainable pace, it should break. If not, then perhaps that word doesn’t mean what I think it means.

In this post, I’ll try to explain what I think many of us mean when we use the “u” word.

First, let me establish the fact that borrowing, by gov’t’s or households, is not bad and is, in fact, essential. Obviously, you want to borrow to spend or invest in useful things with payback, like a college education for a household or necessary infrastructure and other public goods for a gov’t, versus, oh, I dunno, a tax cut for rich people paid for by health and nutritional cuts for poor people. But let us, out of the gate, banish the notion that borrowing is bad. Far from it.

It’s a matter of degree, but how do you measure that degree?

One of the most important ways, elevated in recent years by the economist Olivier Blanchard, is whether your growth rate (g) is higher than your interest rate (r). It’s pretty intuitive: if g>r, then you’re generating enough income to service your debt without adding to it (see here for my earlier writeup on Blanchard’s work for WaPo, with links to his paper). And, for most of our history, g has been greater than r.

Which brings us to the above-the-fold headline in the WSJ that just accompanied my morning coffee: Fiscal Concerns Put Pressure on Dollar and Bond Market.

Investors sold U.S. government bonds and the dollar on Monday, after Moody’s Ratings late last week stripped the U.S. of its last triple-A credit rating, citing large budget deficits and rising interest costs. Adding to the nerves about America’s debt trajectory, the House Budget Committee approved a tax-and-spending bill Sunday that is projected to add trillions of dollars to those deficits.

Moreover, at the same time that the fiscal outlook is pressuring r, tariffs are expect to slow g.

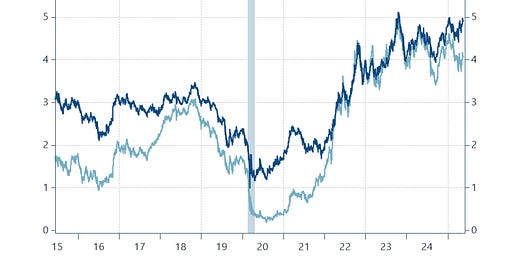

To be clear, these growth and interest rate dynamics are nuanced and highly uncertain. The figure below shows nominal interest rates on long-term and 5-year debt (I choose the latter because it’s close to the blended rate the U.S. gov’t pays on its Treasury debt). In fact, these rates are quite elevated relative to a decade ago, but they’re not exploding.

And while I believe the trade war will slow growth in the second half of the year, it’s hard to say how much. I could see real GDP growth downshifting for north of 2 to south of 2—Goldman Sachs forecasters have ‘25 real GDP at 1%, or 3.2% nominal, which probably means g<r for the year (q4/q4).

These are uncertain numbers, and interest rates are even harder to predict than growth rates. But my point is a simple one: when it comes to debt sustainability, you need g>r. Tariffs lower g; deficit-financed budgets raise r. And—this part is new and important—markets may, as the WSJ piece suggests, be more reactive to the reckless budget part of that equation. “r,” in other words, could be more elastic to the deficit than it’s been in the past.

There’s a second way in which debt is unsustainable, and it’s been working my nerves for years now. The figure shows the unemployment rate (left axis) plotted against the deficit/GDP (right axis, with deficits as positive numbers). Historically, with the usual wiggles and waggles you get in empirical data, these are both cyclical variables. Times get bad, both unemployment and deficits go up. Times improve, unemployment comes down and the return of economic activity increases the revenue flow to the Treasury and deficits come down.

Sources: CBO, BLS

But if you keep cutting taxes, especially for the wealthy, you break that linkage. Good times do not yield the revenue flows they used to. You start seeing elevated budget deficits in good times that look not all that different from budget deficits in bad times. And a gap opens up, as you see at the end of the figure, between the unemployment rate and the deficit. Note the bit I colored in yellow—it’s one of the few periods in a fairly long time series where the unemployment rate goes down and the deficit goes up.

This too, is a signpost on the path toward unsustainability.

Okay, that’s a lot of throat clearing. Out with it, man: what do we, or at least “I,” mean when we say that the fiscal path is unsustainable?!

I mean that the patterns I’m seeing, both in g and r terms and in revenue-flow terms, are likely to put persistently upward pressure in interest rates. This, in turn, will slow growth and force us to divert more of our national income to debt service. Again, if we’re borrowing to invest in things that push the other way—toward stronger growth, more innovation, more human capital—that can ultimately help boost g relative to r. But that’s not even close to what we’re doing.

Note that I’m not saying “unsustainable” means a Liz Truss type implosion, where global lending and currency markets see your fiscal profligacy and turn on a dime against you, “pounding” your currency and spiking your sovereign borrowing rates. US not equal to UK in that regard, due to dollar dominance in global commerce and our deep, liquid debt markets.

BUT no one should take too much solace in such insulation. I know that in these scribblings I always hedge my predictions, as I should. Forecasts are probabilistic—there are no ones or zeros. But on this point, I am unequivocal: incompetent leadership has consequences.

In many ways, this is a very strong, resilient country wherein centuries of democracy, often highly imperfect to be sure, has led to institutions, norms, rules of law, and, in this case, markets that support safe lending to the government. But as we’ve seen so often in recent months, what takes years to build up can take weeks to tear down.

“Unsustainable” has heretofore been an abstraction in our budget debates. With the current leadership, we may find the word is a lot less abstract than we thought it was.

These debates usually ignore the reality that budget deficits (and thus debt) have primarily been driven by Republican revenue cuts rather than federal expenditures. Going back to Nixon presidency, budget deficits explode under Republican Presidents and recede under Democrat Presidents. (Just compare OMB data between the full fiscal year before each presidency and the last full fiscal year of each presidency over the last half century.) When deficits explode, federal debt accelerates.

Republican claims of fiscal responsibility are a sham, based on the data. Efforts to reduce deficits and debt should primarily focus on increasing revenue, especially from the rich, and a return to a truly progressive tax system, which was a key part of America’s past.

Regards, Bill S

The sacred cow - military expenditures, waste and unfunded ghost wars ($2+ trillion) - is missing from this and all conversation.

The GAO highlights abuse regularly to Congress and they continue to not only rubber stamp projects too costly to fly or fail outright (F-35, naval frigates) delays, cost over runs and failures but INCREASE budgets. There is zero accountability or national policy towards projects, such as new nuclear armament programs or this Golden Dome. Both to add $trillions over the next decade.

Military experts and independent watch dogs detail where cost savings could occur, yet it never becomes a national conversation just a black hole of taxpayer dollars and its interest payments added to the debt. But scapegoating the social safety net for working poor, disabled, children and elderly is callously thrown around daily.

Politicians want to talk about waste, well find a mirror baby.