No delusions: Bidenomics wasn't perfect, but it did many great things

Responding to Jason Furman

The economist Jason Furman has penned an aggressive, more-wrong-than-right critique of President Biden’s economic record. Because it’s Jason, a friend and a top-flight economist, there are also good, substantive critiques, and sound arguments from which we should learn. We of the Biden econ team made mistakes, he’s right to raise them, and we should recognize them. It is also very much the case that Jason was frequently and generously supportive and helpful to me and CEA in those years.

But I was surprised to see language more familiar to the Fox news chyron than to a substantive debate: a subtitle reads “the tragedy of Bidenomics;” figures are titled “the Biden Bust” and “Unmade in America.” And there’s a lot in here that I wouldn’t expect from an economist with extensive government experience, who should (and does) know more than he reveals about the intersection of economics and politics. Relative to his usual work, this piece suffers from logical flaws, important omissions, and an unwillingness to deal with powerful political constraints.

The argument is built around the following claims:

--Bidenomics rejected “neoliberal” economics: “respect for markets, enthusiasm for trade liberalization and expanded social welfare protections, and an aversion to industrial policy” along with “an unwillingness to contend with tradeoffs.” It’s advocates and architects suffered from a “post-neoliberal delusion.”

--We were so focused on boosting demand that we a) overdid it, with stark and long-term damaging inflationary consequences, and b) ignored the supply side (this one is a bit odd as he also incorrectly argues that there was no supply shock, just a demand shock).

--Our climate work was well-intentioned and somewhat successful, but it was hampered by our rejection of basic principles. Same with our industrial policy.

--All of this contributed to Harris losing to Trump. Our “missteps reflected a broader unwillingness to contend with tradeoffs in economic policy and allowed Trump to ride a wave of discontent back into the White House.”

Many of these claims are wrong and many fail to recognize economic input from CEA and others that Jason would recognize as sound. Jason devalues remarkably positive economic outcomes from our tenure, and ignores important contributions we made to the living standards of vulnerable families. There are also cases where politics pushed us toward sub-optimal policies, and where we did the best we could with the cards we held. And then there are some important critiques that we should take to heart and learn from.

Fiscal Stimulus and Inflation

Let me start by agreeing with a core part of Jason’s argument. He’s right that the American Rescue Plan contributed to inflation. But, especially given his argument about the impact of this effect on the election outcome, it is essential to try to quantify its contribution. When I and others do so, we find that inflation would have spiked under any realistic counterfactual.

It’s equally important, again in terms of his case, to point out that ARP’s size was not due to a rejection of neo-classical economics nor an embrace of “post-neoliberal economics.” To the contrary, our main talking point back then—one that explicitly admits to tradeoffs—was “the risk of doing too little is greater than the risk of doing too much.” Fed Chair Powell made the same point.

Now, I grant you that this is quantitatively vague. How much is too much? But it is a concern rooted in an awareness of tradeoffs, of which we were as mindful as any economist would be in that situation. We analyzed output gaps, Phillips Curves, and ran standard macro models. Regarding our desire to quickly get back to full employment—a north star for President Biden at this time; he said the phrase five times in a Feb ’21 speech—we’re guilty as charged.

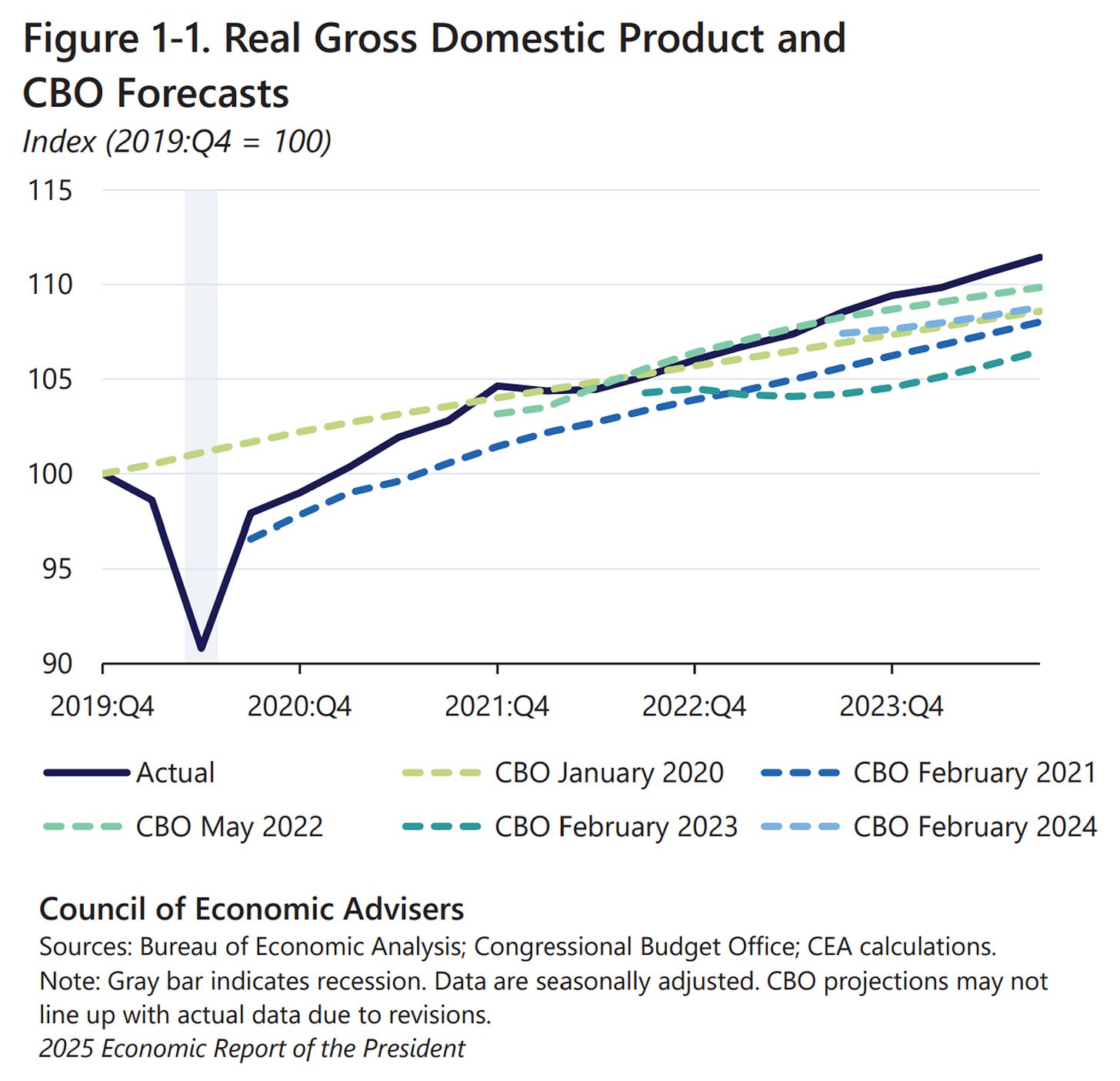

We thought it was extremely important to get families and businesses to the other side of the crisis, to avoid lasting scarring, to avoid business failures and housing evictions. We recalled past stimulus packages that underperformed on these goals, generating initially “jobless” recoveries. In January 2021 we were unconvinced that, even with all the previous stimulus, the economy would power through the pandemic-induced shutdown without the Rescue Plan. COVID deaths were peaking then; the vaccine had not been anywhere close to adequately distributed; we did not not believe the pandemic-induced shock was behind us and we were right: both the Delta and Omicron virus variants were waiting in the wings. The last jobs report we’d seen (December 2020 data, released January 8th, 2021) showed employment down by 140,000 jobs, with the unemployment rate stuck at 6.7%. CBO at the time thought real GDP would remain below its potential until 2025.

There were also political pressures inflating the ARPs price tag. Georgia voters engaged in a crucial runoff for the Senate were promised stimulus checks. Any suggestion to dial them back was shut down by claims that we must make a play for a Senate majority. That’s another tradeoff, familiar to any experienced gov’t economist: sometimes your best economic argument loses to a political one. In this case, the politicos may have been right. There were people who likely got bigger checks than they needed, but Ketanji Brown Jackson is on the Supreme Court.

Where Jason loses me, and, I suspect, others who’ve dug into this, is his downplaying of the impact of the pandemic-induced supply shock on inflation. The ’21-’22 spike in inflation was born of strong demand colliding with damaged supply. You need both to explain what happened. One way to make this case is to show, as we did many times, that inflation went up in all advanced economies (even Japan!), all of whom applied different fiscal and monetary responses, but all of whom had to deal with the fallout from the pandemic’s impact on supply chains.

Jason appears to disagree:

“…the fact that inflation was a worldwide phenomenon does not let U.S. macroeconomic policy off the hook any more than the global nature of the Great Depression or the Great Recession exonerated U.S. policymakers then for their mistakes in managing the economy.”

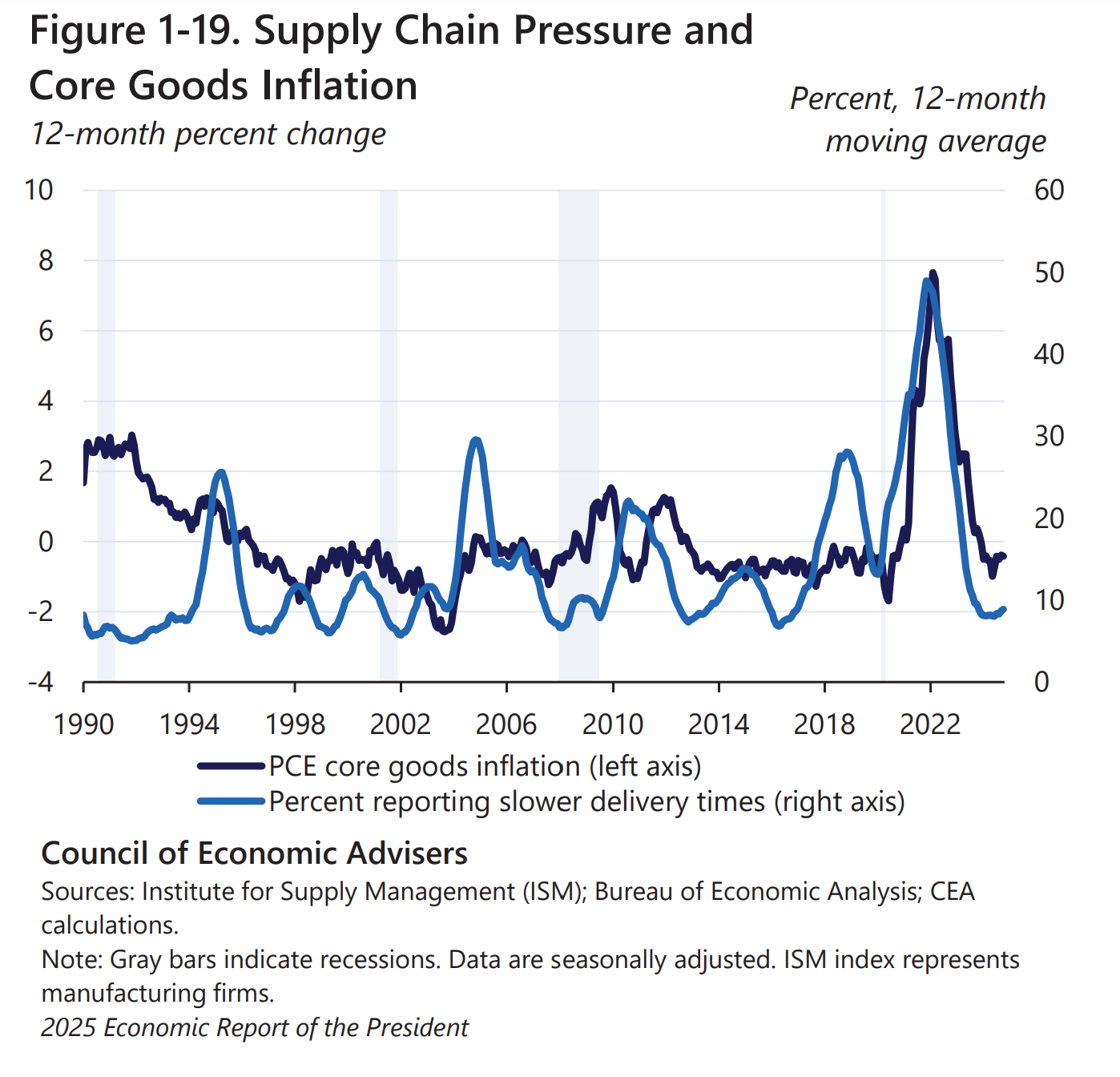

I find it very straightforward to establish the role of supply shocks. I recall chip factories shutting down in Malaysia and elsewhere due to COVID, which led to the numerous-week shuttering of North American auto production plants (a potent example of a non-resilient supply chain, a point I’ll return to below). Various data series that track supply chains showed these dynamics, and their impact on inflation, as in the chart below from CEA’s latest Economic Report of the President.

Here again, unless a bunch of well-established economists, including Ben Bernanke and Olivier Blanchard, are all post-neoliberal delusionists, we’re in good company. Their model also reflects the role of supply chain disruptions, as does work by Peter Orszag, who wrote:

The central cause [of the inflationary spike] was the pandemic itself — and the nearly unprecedented supply-side shock it caused, which extended beyond the crisis itself.

I think Jason disagrees and believes the supply shortfall was itself a function of over-stimulating demand. But there are two empirical problems with his argument. First, as he correctly emphasizes, demand was well above trend for manufactured goods (to which I would add, the very goods that often depend on snarled supply chains to get to markets). But the much larger service share of the economy was in a deep slump and it’s aggregate, not sectoral, demand that matters. As we wrote in the latest ERP: “Because services account for around two thirds of total consumption, the unprecedented services spending shortfall dwarfs the increase in goods consumption over the period of the services shortfall.”

Second, I lived through the damn shutdowns and snarl-ups!

Once you concede the supply shock, then it is the case that even in the absence of the ARP, inflation would have spiked. It’s also worth noting here that contrary to Jason’s claim of “laser-like focus on the demand side came at the expense of addressing impediments to supply,” we worked hard and successfully, in tandem with both management and unions at the ports, to help unsnarl supply chains (which is also how I know they were broken!).

All that said, good evidence, including our own at CEA, suggests that inflation would have peaked lower, perhaps by 1-2 percentage points, without the ARP. However, nobody, including Jason, is arguing there should have been no Rescue Plan. That is a totally unrealistic counterfactual. Had we done Jason’s $650 billion instead of $1.9 trillion, maybe inflation would have peaked at ~7.5-8% instead of 9%. And it matters, inflation-wise, what you’d cut. The $350 billion in state and local support may have been too large given their budget conditions, but those dollars spent out very slowly over many years.

For these reasons, I’m pretty confident that a smaller ARP wouldn’t have changed the public mood very much.

And to do that much less in stimulus would have come at a cost that Jason ignores (more tradeoffs, dude!). As I said publicly at the time, “To the extent that we got more heat, we got a lot more growth for it.” When Jason references macro mismanagement, I think (and hope) that he’s remembering back to insufficient stimulus packages that left the economy underheated rather than overheated.

I’m not unequivocally defending the latter. Like I said, he and others (Larry Summers, Michael Strain) were right about the ARP contributing to inflation, though none predicted it would peak as high as it did. But there’s no outcome here wherein inflation would not have spiked, and the excess demand helped get us back quickly to full employment, staved off a lot of pain and scarring, and set up a uniquely powerful expansion.

Industrial and Climate Policy

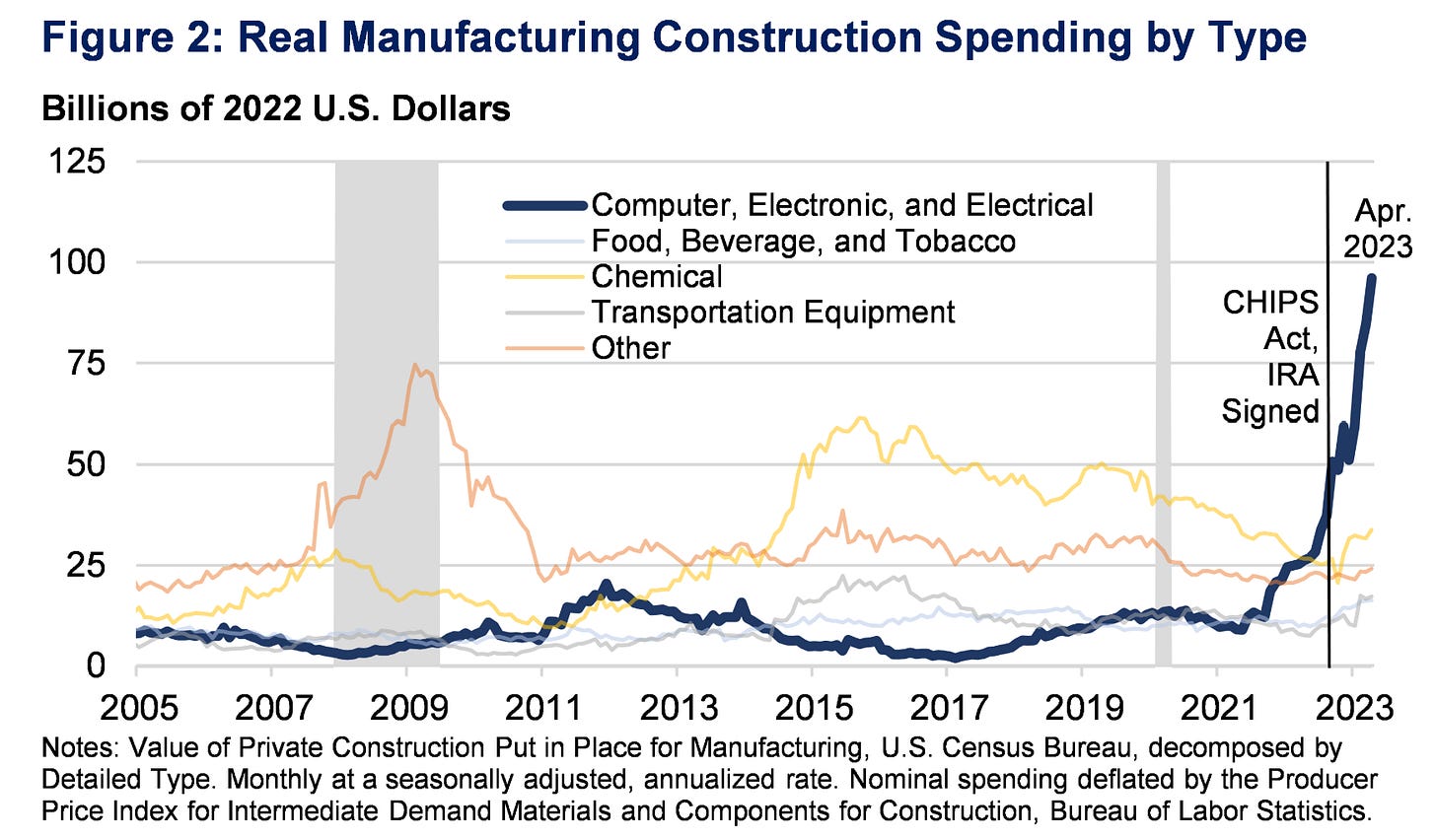

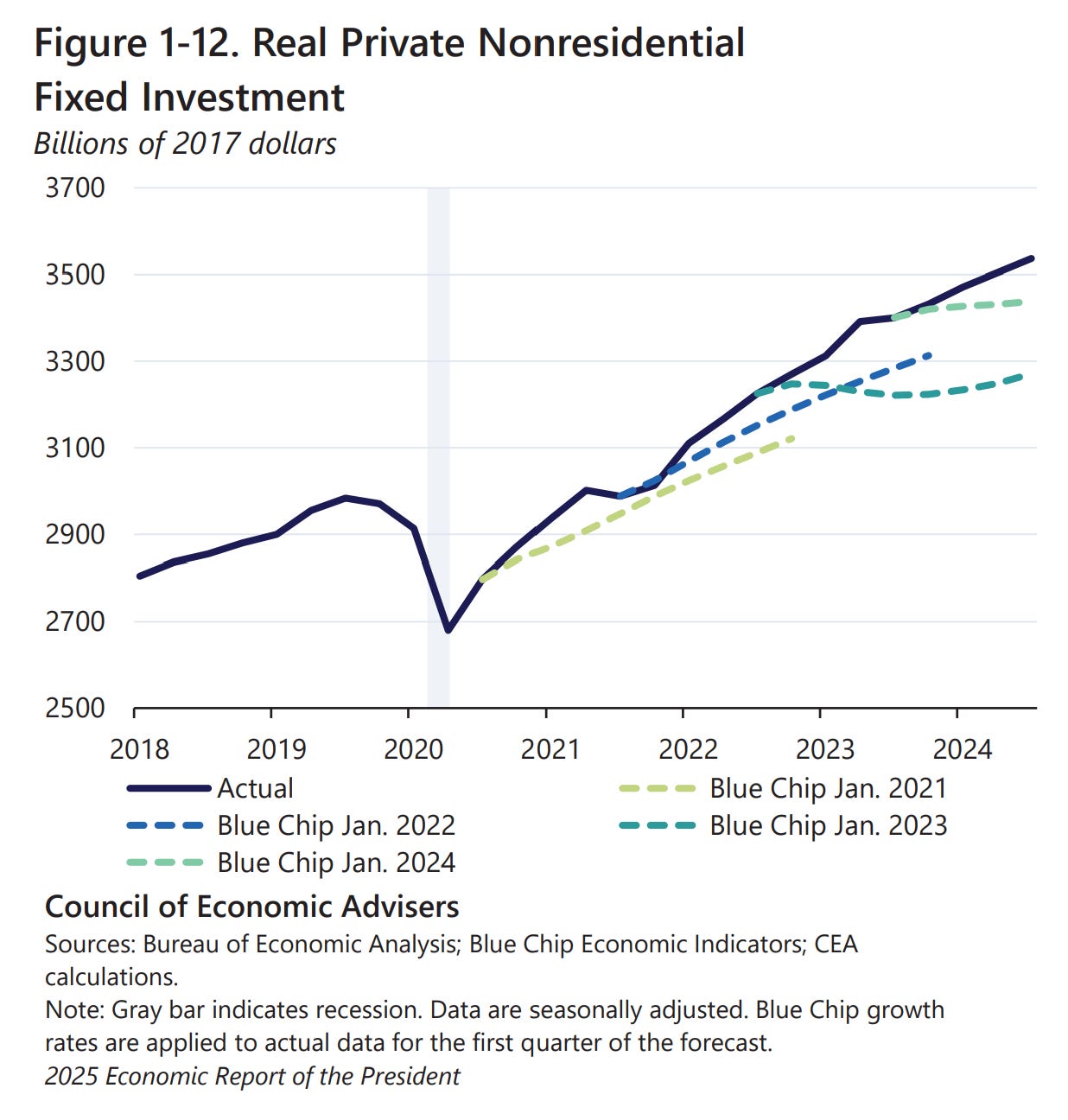

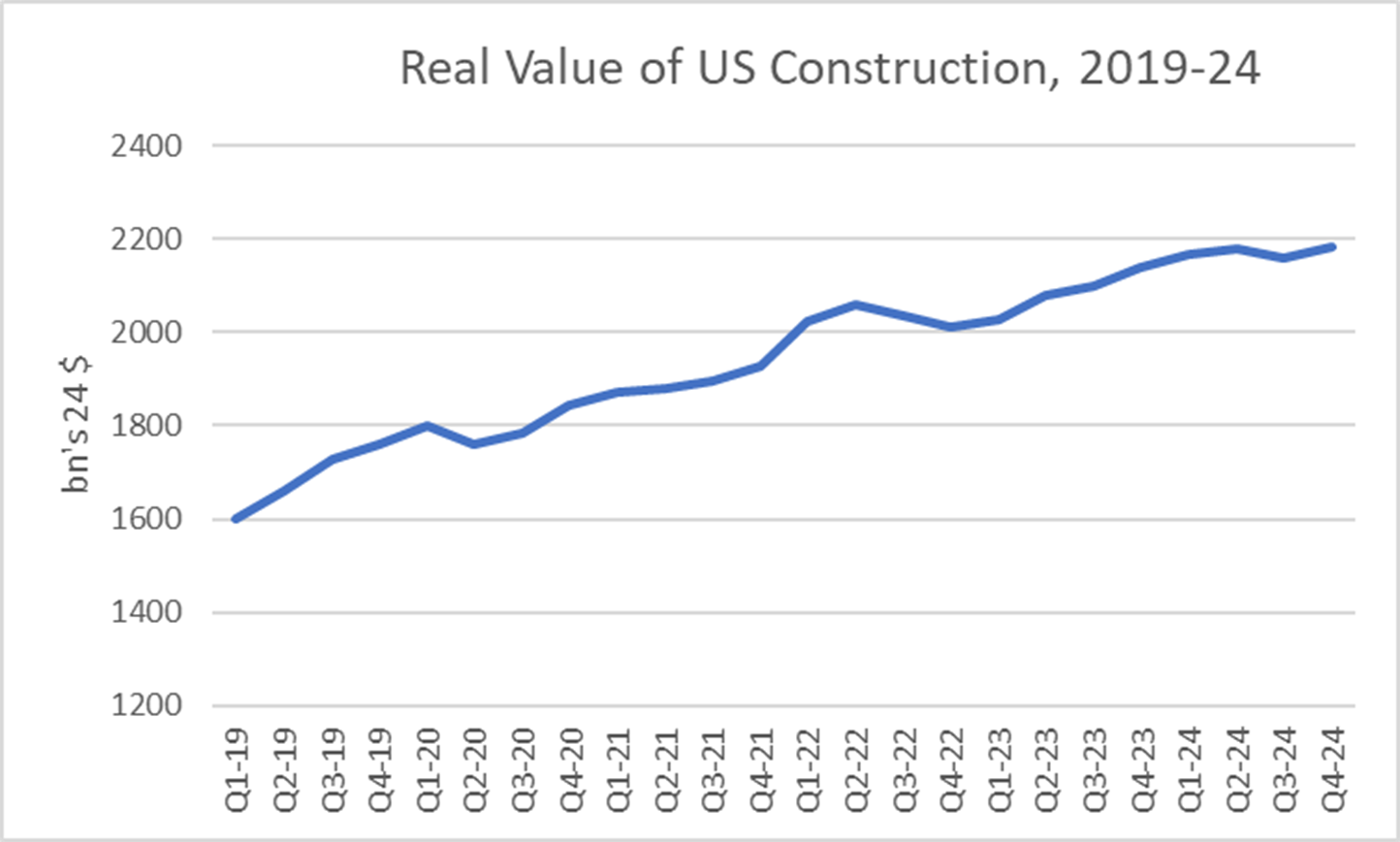

I’m a bit more confused about Jason’s critique of our industrial policy. He recognizes that “an increase in factory construction, which has more than doubled in the last five years” may be a “hopeful sign,” but considers a violation of the neoliberal principle of “aversion to industrial policy.”

This feels like an awfully tame assessment given the empirical record (throughout the piece, Jason weirdly discounts positive economic outcomes; “Bidenomics” can’t just be the parts you don’t like!). The investment incentives we managed to legislate, against tall odds, were pulling in hundreds of billions of private capital, much in the form of foreign investment (see Chapter 6 here). They were standing up a domestic American presence in key sectors where markets were underinvesting.

Which is why his “aversion” point is wrong. Once you define the rationale for industrial policy—government intervention to shape sectoral outcomes—as offsetting market failures that are generating costs to both economic and national security, you’re back in a pretty traditional framework. I suspect Jason and I disagree about the extent of market failures in the spaces we targeted, but I believe I’m on solid ground arguing that left to its own devices, the market would underinvest in climate mitigation. Same with our international supply chain exposure to chip shortages.

Relatedly, on climate policy, I don’t think you could find an economist in Biden world who would disagree with him that the most efficient way to address climate change is to internalize the externality by putting a cost on carbon. But he has to know that a carbon price cannot be legislated. It could not then, and it certainly can’t now. As he admits, “Given the political constraints, Biden’s administration could have done little more to fight climate change.”

Thus, we are in second-best world, and our climate policy scores well in that world, including in the paper he references: “Even at the higher end of fiscal costs, IRA tax credits reduce CO2 emissions at an average abatement cost of $36-87 per metric ton for the power sector—considerably less than recent estimates of the social cost of CO2…”

Once again, no “post-neoliberal delusion” was in play here. We followed the standard microeconomic principle of incentivizing desired behavior to offset a market failure through subsidies and tax breaks. And our approach was comprehensive, with credits for EVs, charging stations, heat pumps, and more. It is certainly the case that we’d get more emissions reduction for a lot less spending with a carbon tax. But that wasn’t in the cards we were dealt and I think we played those cards a lot better than even I thought we could.

What Jason reasonably objects to in this space is a) accompanying addons to achieve other goals in this space, like Buy American or add a child-care function if you want the loan/grant, and b) our failure to do more to clear out regulatory brush that needlessly slowed our progress. These are generally valid critiques, especially regarding permitting, but not all barriers are created equal. “Buy American” is quantitatively too small to distort much and it yields political space to enact important public goods (the Jones Act is a much better target).

The Biden Economic Record

My next objection is Jason’s dismissive take on our record. This surprised me as Jason was among those who made numerous public predictions that it would take much higher unemployment than it did to get the inflation reduction we got. He recognizes that “the U.S. economy has bounced back much faster than it did after previous recessions, and its post-pandemic performance has also outpaced that of many peer countries in terms of economic growth.” But somehow this doesn’t garner us any good-economic-stewardship points for Bidenomics.

I am also hard-pressed to see how this connects to Jason’s theme. We posted strong macro-outcomes and achieved a “soft-landing,” after pulling out of a 100-year pandemic that massively shocked the global economy. Contrary to his claims, we advanced some critical safety net gains. Where does adherence or rejection of neoliberal economics fit into any of that?

He and I also have some data disagreements in this space, which we should work out, because both of us argue such disagreements in good faith. He’s a solid data guy (even if he left out a bunch of links in this piece—bad form!).

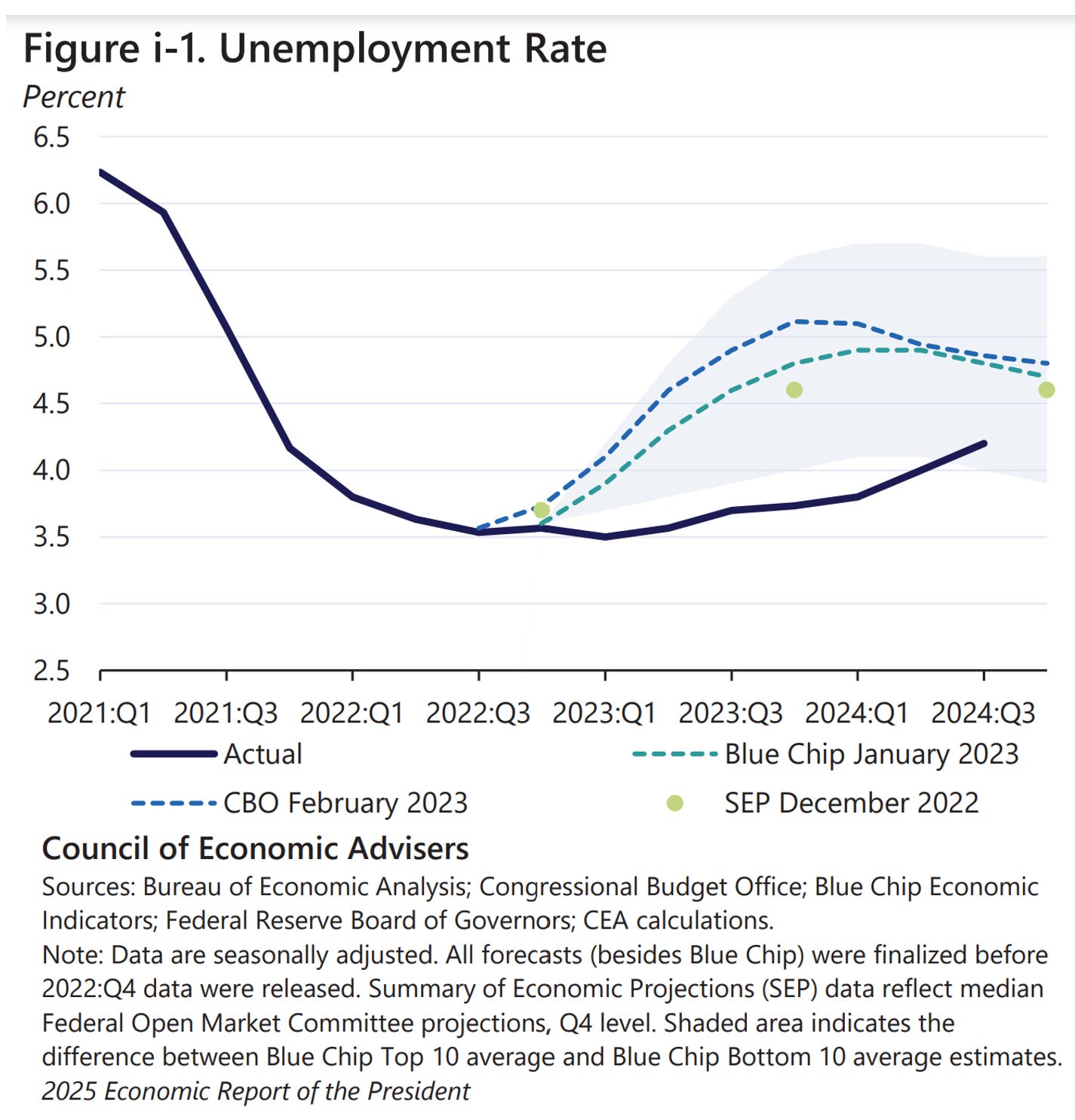

At CEA, we carefully documented the macro record. We didn’t just bounce back faster, we continuously beat the forecasts and expectations, as shown in the figures below for unemployment, real GDP growth, and contrary to what I thought Jason claimed, business investment.

Jason suggested we lost ground on infrastructure spending, but BEA data shows real government investment in structures are up 2019-24, as is real infrastructure spending on transportation on roads, water, airports, etc. But I’m sure we’re using different data here. I’ve also got real construction spending going up, whether it’s investment in building or expanding non-residential structures or real construction spending (Census Bureau data), as in the figure below.

Next, this claim seemed pretty egregious to me: "Biden was the first Democratic president in a century who did not permanently expand the social safety net," probably because I was part of the team that worked hard on what the NY Times called…well, here’s the headline:

It’s not just that this was an important safety net expansion. It’s that we took endless flack from Republicans for it, as we made the change through an administrative rule that instructs us to regularly update the costs and contents of the relevant food basket.

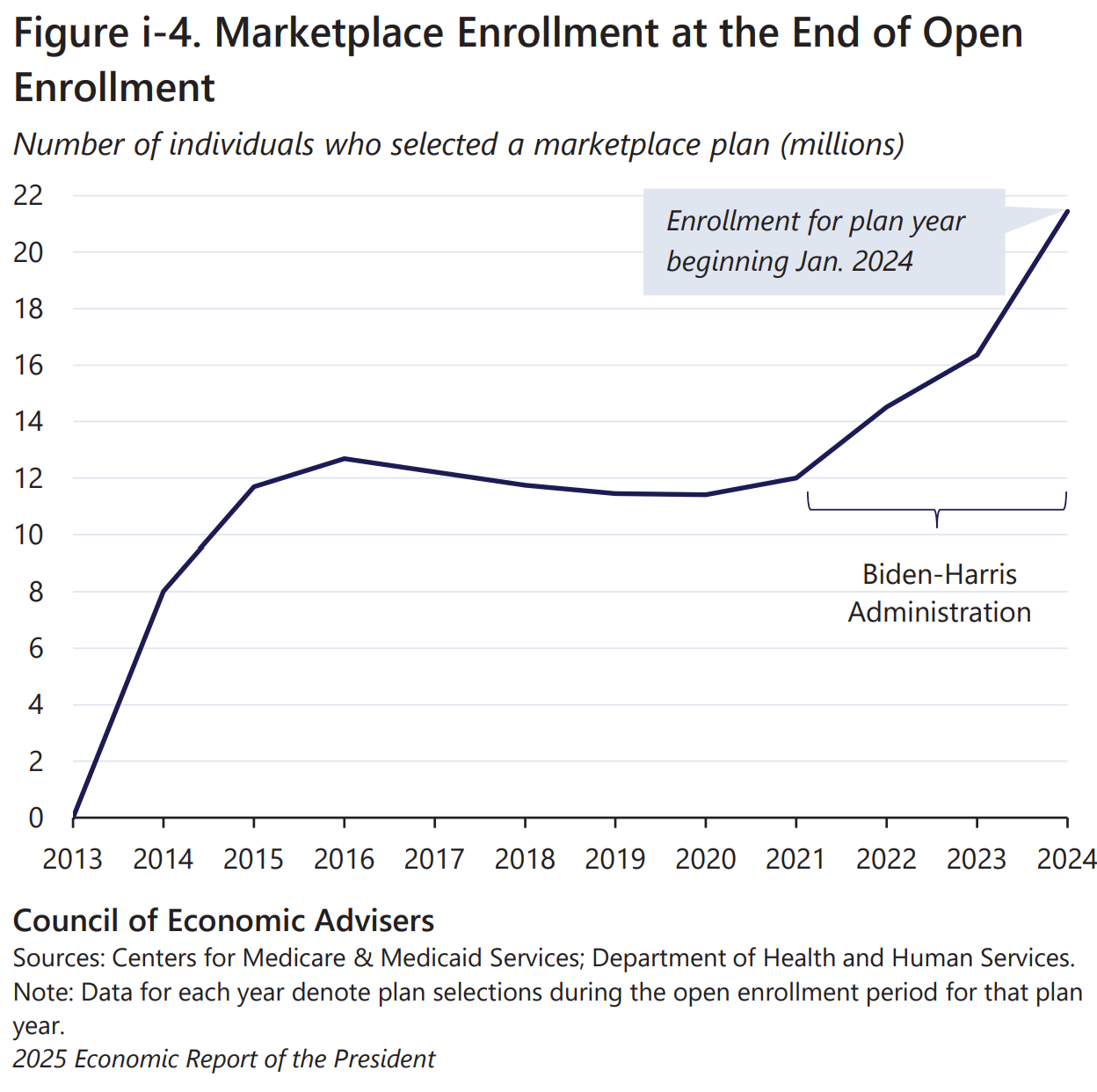

He noted our measures to boost health coverage by raising the subsidies for marketplace enrollment, one we featured prominently in the ERP, though he’s right that, despite our efforts, it was temporary. Of course, as you see given the Trump 1 flattening of the first upward slope in the figure, the Obama administration’s effort suffered the same fate. That’s no more a “tragedy” of Bidenomics than it is of team Obama’s work in this space. It is, however, a stark reminder that health coverage, like child poverty, is a policy variable, and in both cases we fought, unsuccessfully, to preserve our gains.

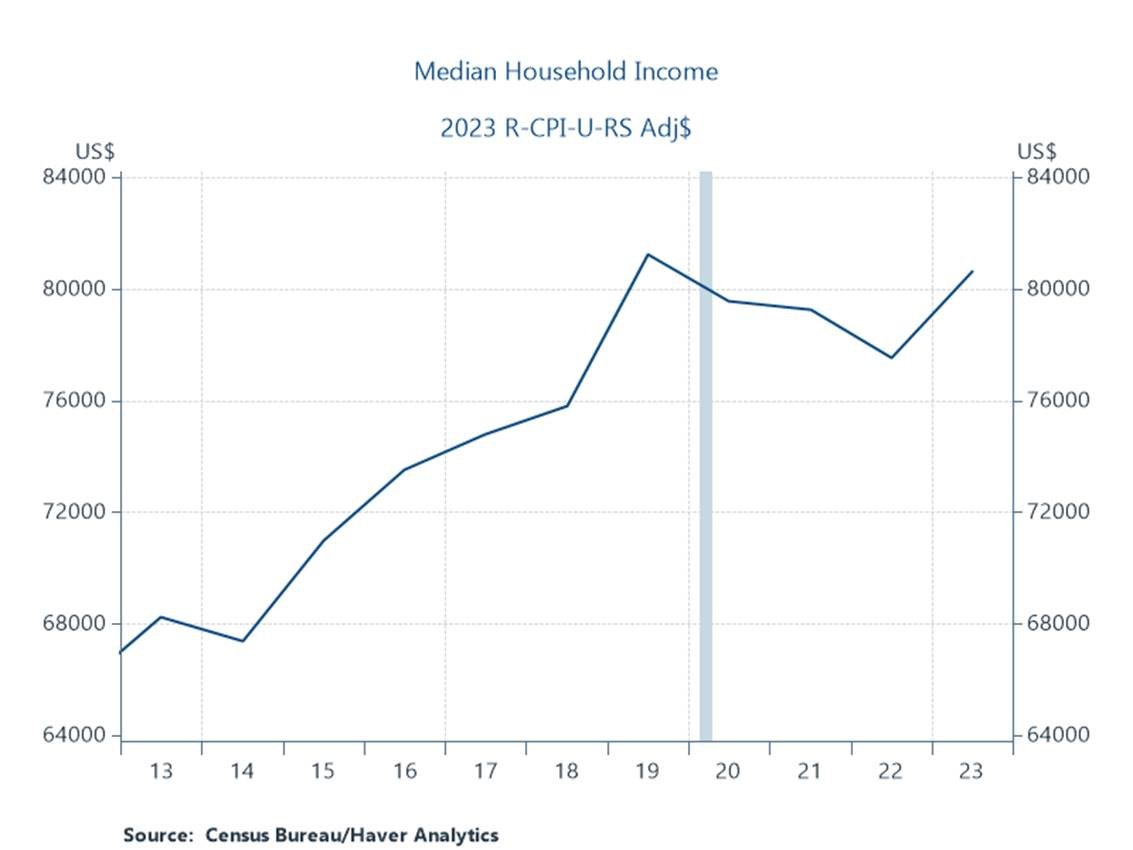

Jason makes a better point regarding real median income, but he leaves out a “future fact” that I’m sure he agrees with. By 2023, this important indicator was almost back to its 2019 level, and I agree with him that this was a source of discontent. However, there are two shortcomings to his case. First, I’m again hard-pressed to see our economic unorthodoxy in play here vs. pandemic shocks which we aggressively fought? If the answer is around the ARP and inflation, go ahead and deflate this series by whatever reduced-ARP-leading-to-less-inflation path you like. I seriously doubt you could plot a series that leads to the median household feeling much better.

Second, this series lags. Jason would agree that this variable very likely maintained its ’23 momentum in ’24. My forecast (and Jason will remind you that I do pretty well with this variable) is that real median income grew 2-3% last year, lifting it about $1,500 above its 2019 level. (The MotioResearch group derives a similar estimate using monthly CPS data.)

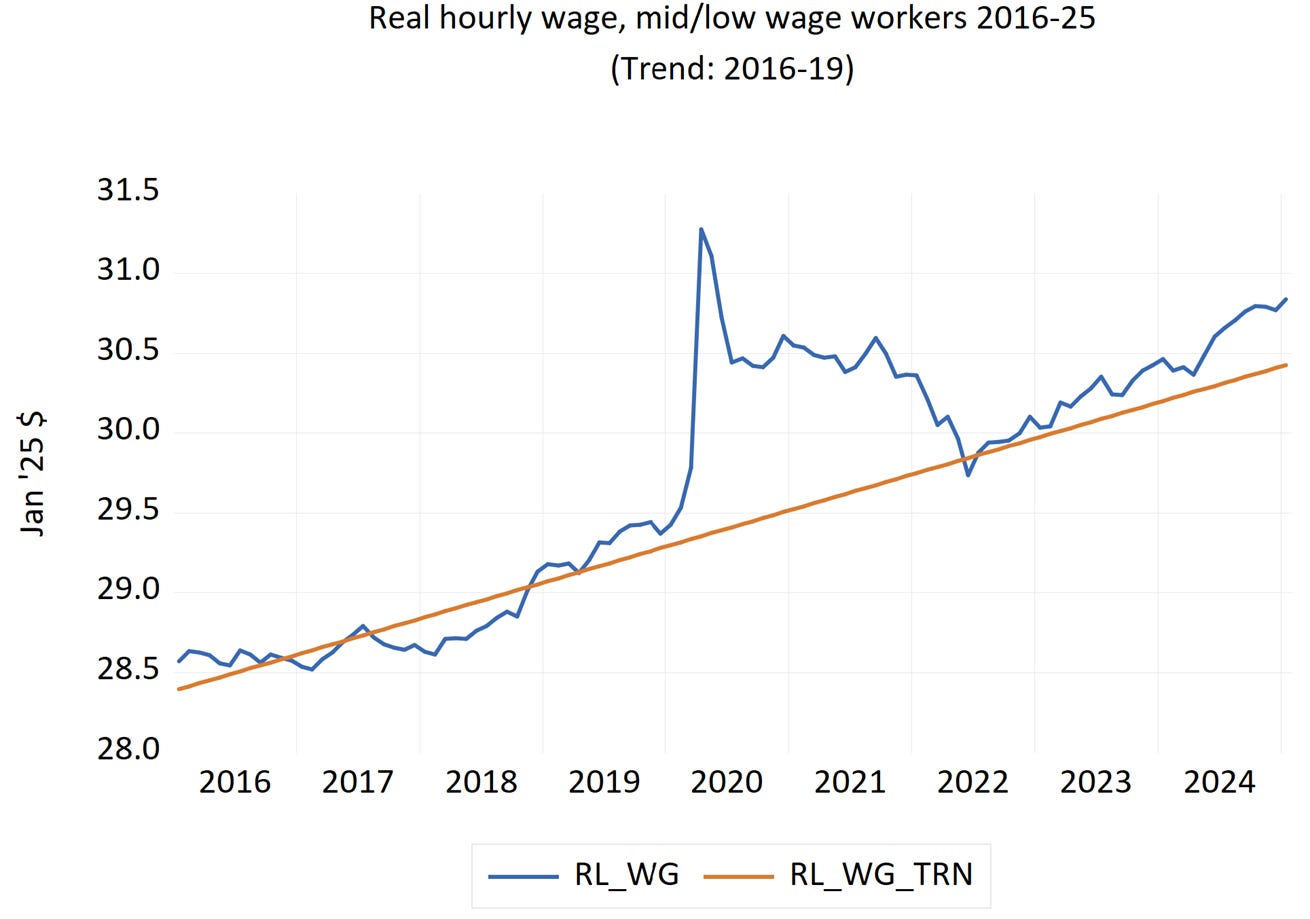

He’s on less solid ground on wages. Besides the Fox chyron title of his wage figure (“The Biden Bust”), I’m not sure he’s using the right data for this. Some of the Atlanta wage series do not track wage levels: the low-wage quartile isn’t tracking workers in the bottom 25%. It’s tracking the bottom quartile of wage changes, which could be workers from any wage level. Its longitudinal framework also tends to down-weight occupational upgrading, which was a positive contributor to wage growth over the years in question. But I could be wrong about this and he and I will straighten this out. Either way, you’ve got to track at a variety of wage series to see what’s going on in that space.

Below, I show the real wage progress of middle and low-wage workers—the 80% of the workforce that’s blue collar or non-managerial. By this measure, they’ve surpassed their 2019 peak and are above their pre-pandemic (2016-19) trend. This is one of the more favorable wage series, but I think it’s better for tracking paycheck-derived living standards than the series Jason plots. And once again, in comparing 2014-19 to the last few years, Jason is comparing macro apples and oranges: he’s comparing the end of a long, strong business cycle with our pretty remarkable emergence from the shock of our lifetimes.

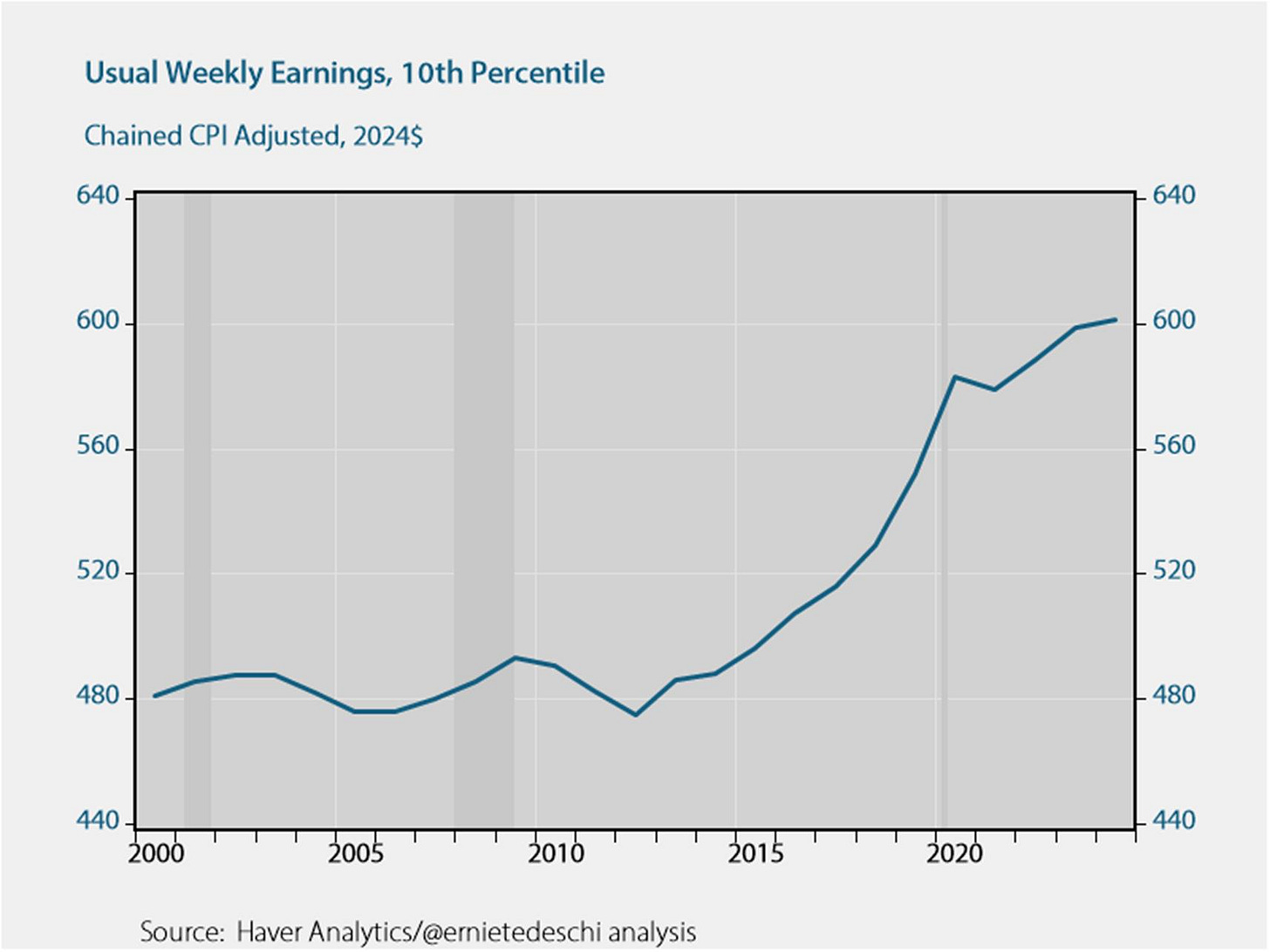

There’s another important real wage series to cover here—weekly earnings (from the CPS)—because it directly relates to the core Bidenomics goal, one routed in classical economics, of sustaining full employment. Our view, elaborated in every ERP I could get my hands on, is that sustained full employment disproportionately lifts the earnings of the least advantaged, and true to form, we see solid real weekly earnings gains by the lowest wage workers (this force was in play pre-pandemic as well).

Wages and incomes recovered a lot more quickly due to fiscal and monetary policies that punched back hard at the pandemic-induced downturn, and in this regard, Bidenomics deserves credit. That said, I of course don’t deny Jason’s point that faster wage and income growth would have likely improved the negative vibes a lot of Americans felt over this period.

Conclusion

Bidenomics had great successes, ones of which our team will always and rightfully be be proud. The incoming administration were met with a uniquely strong macroeconomy and labor market, with years of full employment, easing inflation, and real wage and income gains supporting strong spending and solid investment. Jason and others predicted that it would take much higher unemployment to get to where we are, but we left with a soft landing in play.

Bidenomics also had shortcomings. We didn’t do enough, as Jason reminds us, to take down barriers to progress such as permitting and other such obstacles. We left the field with unfinished business in the supply of affordable housing and child care. The ARP contributed to inflation; it would have spiked no matter what, but less so if the ARP had been smaller. But the package was born of both great, pandemic-induced economic uncertainty of the moment and political pressures that added to the price tag.

We never abandoned basic economic principles like tradeoffs or faith in markets. We did see more market failures than Jason does, and he and I should argue about that. But to conclude on the basis of the extensive empirical evidence I present here that Bidenomics was a tragedy, or that it sank Harris’ electoral chances, requires a rewriting of recent economic and political history that does a great disservice to an administration that worked as hard as we could on behalf of the American people.

[I kinda suspect Jason will want to react to this. That’s as it should be, and perhaps, if I can figure out how to work it, he and I could film a video for this Substack. I know I learn something every time we talk!]

I'm generally a great fan of your work Jared but you are giving way to much credit to Jason. The failure to defend Bidenomics as illustrated in this piece was a big part of the problem.

The only decent coverage Biden got came in the industry blogs - farming, shipping, manufacturing, solar, etc You'd never have known he sent hundreds of millions to make ports emission free, efficient, lowering the cost of transportation and goods, helping supply chains, if not for the maritime industry - coast to coast, east and west. A priority of Harris since her days in CA where she tackled port community polluters with fines for crimes. Booze got a boost when Joe's Commerce got tariffs eliminated for bourbon - So much more that you only read about if you were on the agency home pages (Interior, Transportation, Commerce, Energy, EPA) or scoured the blogs and local digital reporting - Shame.