Paul K, Michael P, and Trade Balances

It's a weird time to talk about rational trade policy, but here goes...

[You know how Paul Krugman tells you that the following is economically wonky and longer than usual? Well, that’s the case here, and it’s also riffing off some of Paul’s recent work on trade policy—not so much tariffs, per se, but they’re in there somewhere. BTW, I suspect many of you are enjoying unleashed Krugman as much as I am!]

Thoroughly enjoyed this analysis by Paul Krugman on why some of the “new” thinking on trade policy is wrong. Paul respectfully criticizes work by Michael Pettis, someone I’ve closely followed for a long time in this area and while there’s nothing in Paul’s presentation I disagree with, I do think Pettis deserves credit for pushing back on some earlier wrong thinking in trade policy, a key pillar of which Paul agrees with: trade imbalances can be caused by distortionary policies.

To this day, many trade economists insist that trade imbalances are always and everywhere benign reflections of relative macro conditions and the savings-investment identity. Back in my EPI days in the early 1990s, when we began to worry about what would later be called the China shock, the typical response was some version of: don’t you dopes know that the current account balance is savings less investment. If you want more balanced trade, just save more!

Pettis, and others, including Bernanke, have argued it’s not that simple. When other countries suppress domestic consumption and export their excess savings, either in capital flows that can inflate bubbles, or manufactured overcapacity that undercuts domestic manufacturers (which is what we mostly meant by “unfair trade” in the Biden admin), they can create big problems here that are as much of their making as of our own.[1]

But this is a sidebar to Paul’s target, which is that trade imbalances are not an obvious problem, the trade deficit is no kind of score card (sorry President Trump and even more so, Lighthizer), and, perhaps most important in terms of looking forward, there’s nothing wrong with jobs in services. On that last part, I would have added, especially as it was a Biden CEA theme: while we’ve consistently run trade deficits in goods, we’ve also consistently run trade surpluses in services (the latter much smaller than the former of course, but still…).

Paul’s points beg the question: what should we do with this information, especially now when trade policy seems in pretty serious trouble? That’s a tough one, for sure, but first, how is trade policy in trouble? Let me count the ways.

Three ways trade policy is in trouble

First, based on my recent experience in gov’t, the political incentives are to eschew international cooperation, creating a toxic climate for the policies implied by Paul’s lecture. Re China, I can tell you that if I proposed to Congress that we introduce a national holiday in my name, it would go nowhere unless I made the case that it would hurt China. Then we’d all enjoy a day off for JaredDay. But under Trump, the same is true for our friends (I see you Can and Mex!). Such geo-phobia is highly destructive.

Second, trade is trouble because not just tariffs, but sweeping tariffs appear to be more politically popular than ever. Targeted tariffs—I’m talking rubber-tires-grade-4—are a tried-and-true trade tool. This other stuff ain’t that. Aside from price effects hitting both consumers and producers that use imported inputs (which comprise about half of our goods’ imports) and retaliation risk, trade policy uncertainty is off the chart, and that’s been shown to hurt investment (note that you get this effect even if you’re bluffing, as President Trump appears to have been).

Third, and also stressed by Paul, manufacturing jobs are elevated by policy makers with little interest regard for services. But both are important. There’s no politics, nor should there be, in taking a c’est la vie attitude toward the loss of factory jobs. Paul’s right that their quality has deteriorated, but from what I learned in the Biden admin about the jobs associated with the new factories coming on line, this could change. And the downstream spillovers, many of which enhance services, are important to left-behind communities, where the majority of this investment is taking place.

But as Paul’s German example shows, the share of manufacturing jobs trends down even trade surplus economies (although his slide on this shows more stability to the German manufacturing share than I thought). Moreover, even with a (measured[2]) productivity differential, there’s no reason why service jobs shouldn’t be better. Getting there requires maintaining full employment, expanding service unions and bargaining power, but also requires society to value teachers, child-care and health-care workers a lot more so than we do.

What now?

It feels a little embarrassing arguing these facts and nuances right now, but that is what we do and I don’t think we should stop. So, how do we get from where we are to where we need to be on trade?

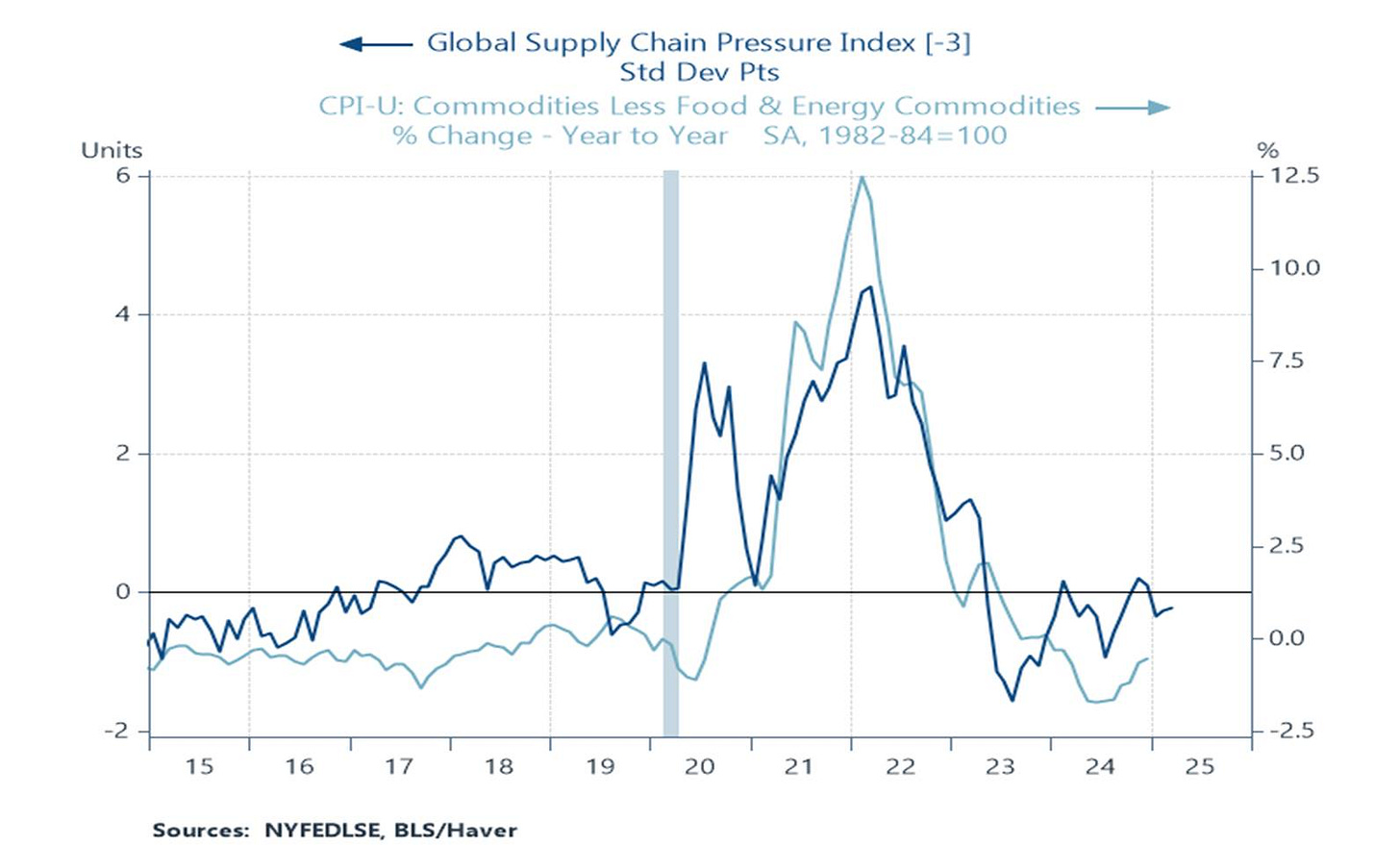

First, we should elevate predictions of the harm done by sweeping tariffs and full-on protectionism. Pandemic inflation is not yet forgotten by average folks, and that period unequivocally showed that constraining the flow of goods and services, aka, snarling up supply chains, is inflationary and highly discomforting.

Here’s core goods inflation plotted against a lagged supply-chain measure. I understand and worked on the Biden admin’s move to develop domestic supply chains, e.g., chips. But more trade openness and cultivating good will with our trading partners is also essential to maintain non-inflationary supplies.

Second, at Biden’s CEA, through ERP chapters and blogs, we pursued what we thought was a sweet spot in this debate that respected Pettis arguments about trade distortions, recognized both benefits and costs from trade, and argued that there’s ample room for both more domestic production, often financed by FDI, alongside robust trade flows, though less with China and more with others. This both/and agenda grew out of work by an impressive group of international economists—Kari Heerman, Sandile Hlatshwayo, Fariha “trade-services-surplus” Kamal, and Anusha Chari. They worked hard to understand both sides of the equation and get beyond “if it says free trade on the cover, I’ll sign it,” and “trade deficit bad!!” Their work complements Paul’s rap and, should you want a deep dive, is worth your time.

[1] Maury Obstfeld makes a characteristically muscular argument that while this excess savings story is plausible, it is “oversimplified and therefore incomplete,” relevant in some recent years but not in others. https://www.piie.com/sites/default/files/2024-08/pb24-7.pdf

[2] For Baumol reasons, there are productivity measurement constraints in comparing manufacturing and service wages: it’s not more productive to play the 3-minute waltz in two minutes, nor to double class sizes, though both would register as higher productivity.

Jared, I need to be completely honest with you. I appreciate your insights, and your ability to frame these debates in a way that makes them accessible without losing depth. But reading the news these past few days—and seeing how U.S. trade policy has played out over the last few years—has put me in such a state that I apparently blacked out and wrote this entire essay-length comment. I can only assume my subconscious, outraged by the sheer absurdity of watching America punch its allies in the face again, took over my hands and started typing in a fit of despair.

It is appalling to see allies and close friends—Canada, Mexico, the EU—treated with such disdain, as though they were trade adversaries rather than partners essential to our economic and geopolitical security. And while Trump’s return has escalated things to an extreme, let’s be real: the groundwork for this moment wasn’t just laid by Trump. It was also shaped, in part, by the trade policy under the Biden administration.

I know the political climate was difficult. I know that after 2016, “free trade” became politically toxic in both parties. But what I struggle with is how the Biden administration—rather than correcting the reckless protectionism of the Trump years—chose instead to validate it in too many ways. Rather than making the case for a strategic, pro-allies trade agenda, the administration hesitated. It retreated into a defensive crouch, leaning into tariffs, Buy America provisions, and an industrial policy that often signaled to our closest allies that they were an afterthought, not a priority.

And here’s where I have to talk about Katherine Tai.

I get that she was navigating a tough political reality. But her tenure at USTR felt defined by indecision and missed opportunities. Instead of reasserting U.S. leadership in global trade—rejoining the CPTPP, pushing for a deeper economic partnership with Europe, offering real market access in IPEF—she presided over a trade policy that was largely protectionist, reactive, and unambitious. The idea that the U.S. could somehow counter China without building deeper economic ties with its allies never made sense. And yet, that’s effectively the approach the administration took.

Then there was the tariff question. Keeping Trump’s tariffs in place was bad enough, but Tai’s insistence that tariffs weren’t driving up prices was, frankly, damaging. The data said otherwise. Multiple studies said otherwise. And yet, rather than make the politically tough but necessary argument that tariff relief could ease inflation, she gave Trump an open lane to claim vindication. If Biden’s own trade representative wasn’t willing to say that protectionism was costly, how could Democrats expect to run against it?

And now, in 2025, we’re living in the consequences. Trump is back, escalating trade wars on all fronts, dragging the U.S. further into economic isolationism, and alienating allies at precisely the moment we need them most. And the most frustrating part? This could have been prevented. The alternative was there all along: a strategic trade agenda, one that balanced industrial policy with real economic integration, one that prioritized friends over tariffs, one that understood trade as a tool for collective strength, not a zero-sum battleground. But that path required boldness. It required taking political risks. And for the most part, those risks weren’t taken.

I know you understand all this better than almost anyone. At some point, we have to ask: What happens when those constraints become the policy itself? Because that’s what I fear happened with Biden’s trade approach. The administration didn’t just acknowledge the post-2016 protectionist shift—it internalized it. And in doing so, it left the door open for Trump to return and take things even further.

So where do we go from here? I completely agree with you that we need to be louder about the economic costs of sweeping tariffs. But I’d take it a step further: someone—anyone—needs to start making the full-throated, unapologetic case for trade as a source of American strength, not a political liability. Right now, the debate is entirely shaped by its opponents. And unless that changes, we’re just going to keep losing ground—economically, diplomatically, and strategically.