Tuesday's Mashed Potatoes

Getting ready for T-giving, here's a mash up: a few numbers of interest, and Greg Ip says affordability can't be solved and is therefore a loser for incumbents.

Source. I prefer latkes fresh out of the frying pan, but a pile of mashed will grace my plate on Thursday.

Just How Much Is AI Juicing Growth?

We now have a least two front-page articles and many notes from finance shops underscoring, and flagging for concern, the extent to which overall growth rests on AI investment. It does so through at least two channels, though its advocates claim a third will be forthcoming.

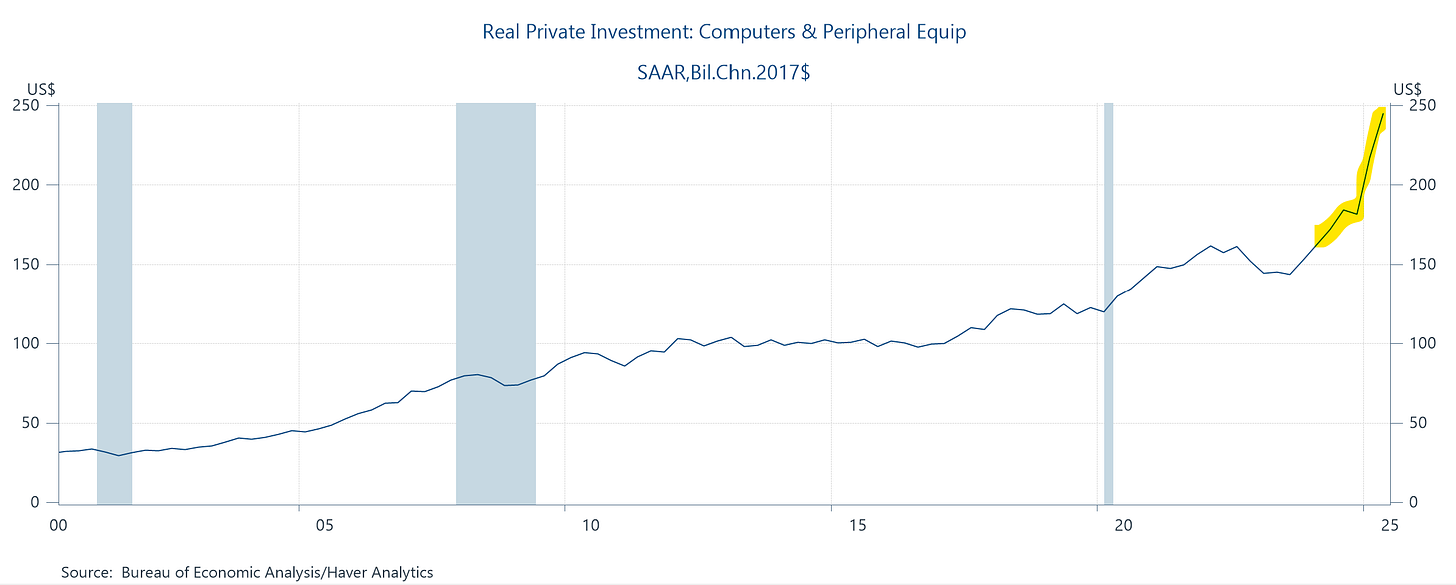

First is the straightforward, direct “capex” (capital expenditures):

The NYT uses a measure like this to come up with a pretty blockbusting number: “…investments in computer equipment and software accounted for more than 90 percent of growth in gross domestic product in the first half of the year.”

They warn that we shouldn’t read too much into that huge share because perhaps the capex would have flowed elsewhere, but that’s not the main problem with this inflated share. That would be that it includes imports, which surged of late in an effort to front-run tariffs.

The WSJ cites more measured, but still very large, growth effects:

Chips such as those sold by Nvidia make up the bulk of AI spending, but most are imported and must be subtracted from total investment to arrive at the impact on domestic production. Accounting for that, AI spending still increased output by an annualized 0.8% in the first half of the year, Barclays estimates. GDP grew by an annualized 1.6% during the period. In other words, absent the growth in AI-related spending, growth would have been a sluggish 0.8%.

The second channel through which AI juices growth is the wealth effect, which I’ve written about a lot up in here.

JPMorgan Chase calculates that rising prices of AI stocks alone boosted consumer spending by 0.9%, or $180 billion, over the past year. Though a small part of the 5.6% growth in consumer spending in the 12 months ended in August unadjusted for inflation, that still matters because consumption accounts for about two-thirds of annual output.

Third would be longer-term growth effects which have yet to show up and, of course, may never do so. I personally find it hard to figure out how AI won’t contribute something to faster output-per-hour (productivity growth) but it takes years for such effects to show up. Here’s a useful summary of the work on this wherein you’ll note many outsized predictions, like GS’s doubling of productivity growth. That would really be something, though not unprecedented:

We estimate that widespread adoption of generative AI could raise overall labor productivity growth by around 1.5pp/year (vs. a recent 1.5% average growth pace), roughly the same-sized boost that followed the emergence of prior transformative technologies like the electric motor and personal computer.

Others predict a surge in productivity growth that raises its level but then reverts back to its earlier growth path. I wouldn’t spend a lot of time noodling on these outcomes, as you know my methods in such cases: hope for the best, plan for the worst. Which in this case means being ready with a jobs guarantee program in case AI evolves, unlike past technologies, to be massively dis-employing.

The point of these articles, which is correct in my view, is that the extent to which the U.S. economy is being driven by AI capex and wealth effects creates a macroeconomic fragility. You want a much more diversified growth portfolio than we’ve got, and while building data centers can employ 1,000’s of workers, staffing them can employ fifty’s of workers.

All the more reason for the bubble-watch I’ve emphasized in various places.

Is 4.4% Still “Low” Unemployment?

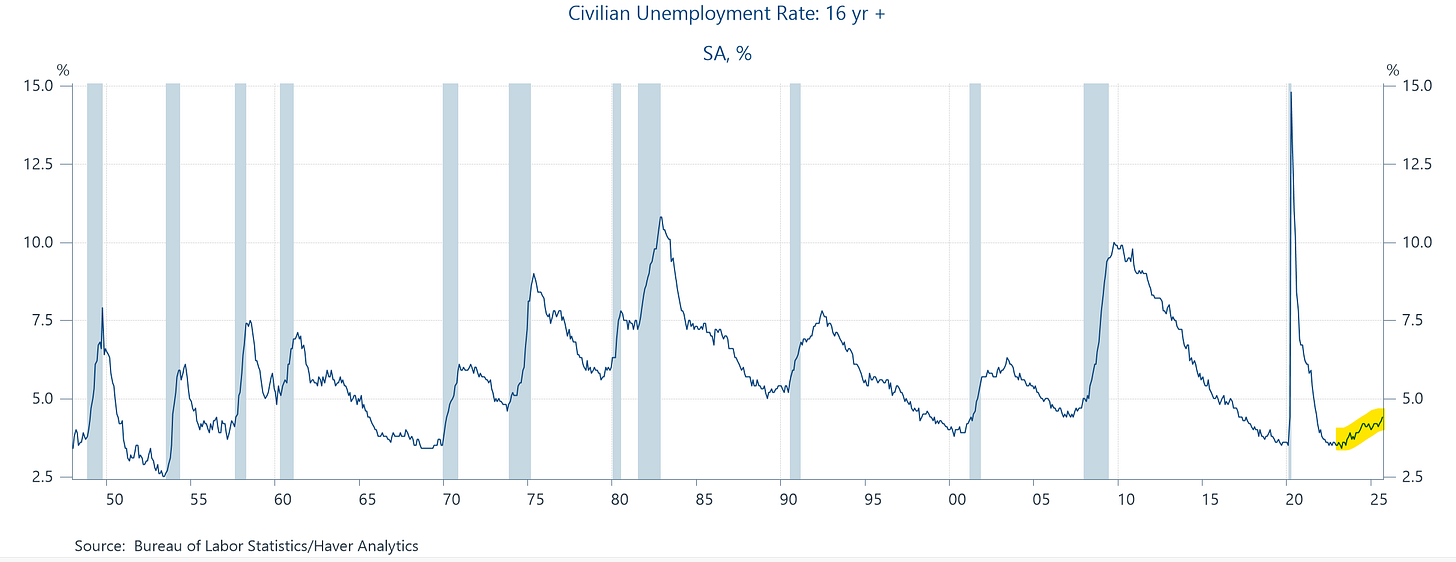

We in the econ-punditry (along with Fed chairs and govs) often say some version of “Yes, the unemployment has gone up but it’s still very low.” But, at 4.4% when last seen in September, is it?

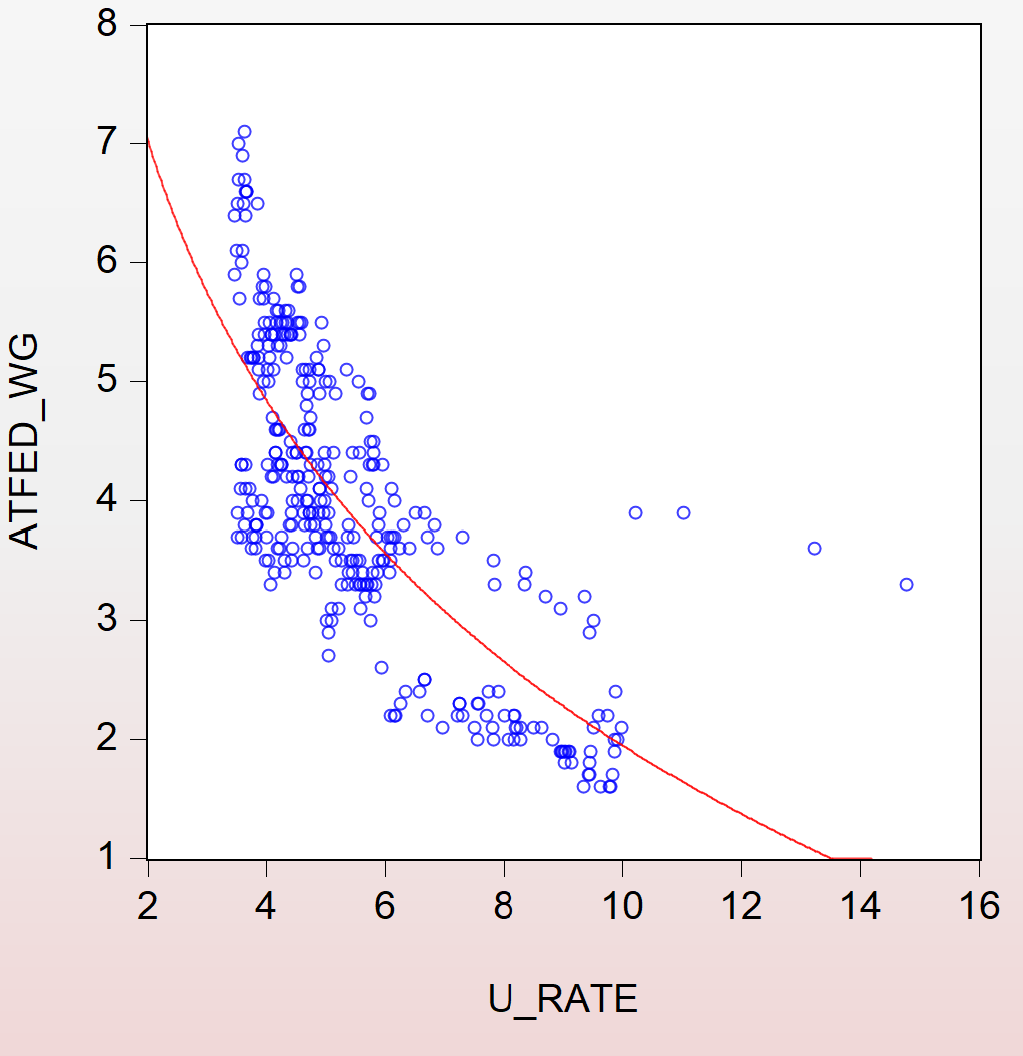

It’s a full point above where it was in April of ‘23. And as the figure below shows—a scatterplot of yearly nominal wage growth from the Atlanta Fed series against the unemployment rate, higher unemployment means slower wage growth, with a steep part of the non-linear (log) curve right around where we are now. So, this is costly for workers, especially for workers of color, whose jobless rate is often multiples of the overall rate.

Hold up: isn’t there are danger that lower unemployment will boost inflation? But inflation was falling when the u-rate was in the 3’s, and pre-pandemic madness, the correlation between unemployment and inflation was known to be low (for the initiated, I’m arguing that the Phillips wage curve has more of a slope than the Phillips price curve).

In historical terms, 4.4% is at the 28th percentile of the distribution of the monthly rate since 1948, but because changing demographics affects the level—more young people in the labor force tends to mean higher unemployment—you want to look over shorter periods. Starting in 2000, 4.4% is the 34th percentile, so maybe not all that low.

On the other hand, it does just about match the CBOs estimate of the “natural rate,” the unemployment rate at full employment, which is 4.3% for the current quarter.

So, which is it? Others should weigh in (Dean, Claudia, Ernie, Guy, etc.), but imho, 4.4% is not very low unemployment. In my work with Dean, we considered unemployment at full employment to be in the 3.5-4% range, and thus 4.4% with an upward trend is sub-optimal from our critical perspective of providing middle- and low-wage workers with the bargaining power they need to get a fair shake.

Is Affordability a Loser Agenda??

The always interesting Greg Ip argues that affordability, one of my go-to topics up here, is amorphous, poorly-defined, and unsolvable. Coincidentally, this follows a dinner gathering the other night wherein a wise friend of mine made a similar point from a political perspective, essentially arguing, as does Ip, that it might be fine to campaign on, but you can’t successfully deliver on it.

And these are fair points. I mean, can you imagine a substantial chunk of the electorate saying, “yeah, I’m good now, affordability-wise?” Politically, no question that affordability concerns are much easier to attack from the outside than solve from the inside. Trump right now is exhibit A of this truth.

But I still disagree with the thrust of these arguments, or at least I have a very important amendment. Greg is right that no one is going to lower the overall price level. That takes a deep recession and nobody wants that.

Yet it is demonstrably wrong that policies cannot increase the affordability of key goods and services that are both essential and too expensive for too many given the inadequacies of market production in these areas. They include healthcare—which is far from a competitive market in the first place—housing, childcare, utilities. Some add groceries to the list, and I hear them, but even while there’s some degree of industry concentration in the sector (and thereby inadequate competition that could lower prices, or at least price growth), it’s a pretty competitive sector and I’ve always been wary of policy’s ability to do much there.

So, I declare both sides right here. No one can or should try to lower the overall price level. But an affordability agenda that crafts careful, well-designed policies that follow the three-legged stool (reduce regulatory sludge, subsidize where needed, increase competition), targeting a few key areas where the essentials of life are too out of reach for too many Americans is non just good policy. But, it’s good politics.

Really? Even if you can’t deliver?

No question, you’ve got to deliver. But if you fight tooth-and-nail in this space, and people see you doing so, and you’re emphatic about who’s blocking you (and thereby preserving their “rents” at the expense of the rest of us), then yes, I suspect it can be good politics.

Glad to see you use the amputee economist aphorism, “On one hand …”.

Let’s pick one element of “affordability,” .. childcare. Mamdani and NYS guv Hochul are discussing an income-based childcare tax targeting, in the beginning, the most economically marginalized communities… yes, complicated, but, a huge political winner. It’s not resolving affordability, it’s the perception that you actually acknowledge and are addressing, even if only one aspect

Wait! You forgot today's "MUSICAL CODA".

(Don't worry. I've got you covered.)

MUSICAL CODA

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qMxwef3W_0c&t=9s

----

Whoops! I seem to be mixing up the economist substacks.

Never mind.