In response to this post, “Wi” leaves a thoughtful comment, one that warrants a response.

As I would frame it, my post argued for what we in Biden-econ thought of a “both/and” trade policy, which I also think of as “group 3” policy. IE, at the risk of mild reductionism, there are three groups in this trade debate. Group 1 thinks that the benefits of international trade are many multiples of the costs. Economists like Jason Furman, Maury Obstfeld, Kim Clausing—fit here and each makes a strong case.

Group 2 thinks that ratio is flipped, which is where team Trump is. Group 3 recognizes more costs than Group 1 and more benefits than Group 2. I’d put myself in there and would argue that’s what we’d try to pursue in the Biden administration.

Wi, and he’s not alone, disagrees: “the Biden administration—rather than correcting the reckless protectionism of the Trump years—chose instead to validate it in too many ways.” And: “The administration didn’t just acknowledge the post-2016 protectionist shift—it internalized it. And in doing so, it left the door open for Trump to return and take things even further.”

Another way of expressing this argument is to go back to Jake Sullivan’s Brookings speech where he talked about trade restrictions in the spirit of “high-fence, small yard.” Wi and others would say the yard turned out to not be so small.

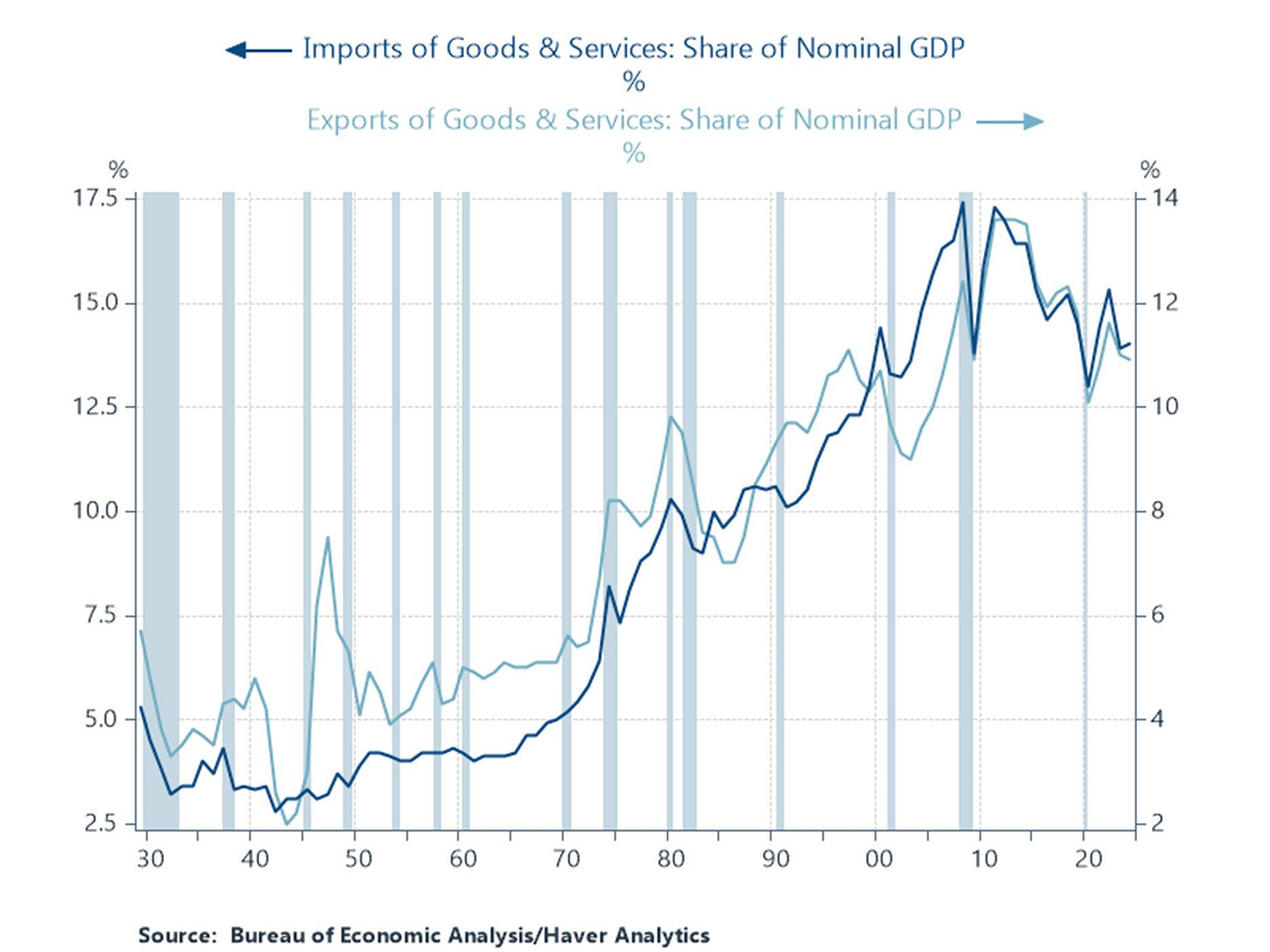

At one level, the data challenge that assertion. Trade flows remained pretty robust. The trade balance (first figure below) hovered around -3% of GDP (and note that despite their claims to the contrary, Trump 1 didn’t change this variable either). The 2nd figure shows that import and export shares (of GDP) have trended down somewhat since their 2010 peak, but re their levels, hard to see a lot of effective protectionism in those data.

But there is also evidence to support Wi’s claims. As he said, we kept Trump’s China tariffs, and added some of our own, exclusively targeting China.

On the economics, I think that’s defensible. If Costa Rica was suppressing domestic consumption to generate excess savings that were then mercantilistically deployed through manufactured exports, we wouldn’t notice it. But when an economy of China’s size does so, that’s a problem for us, which we discussed under the rubric of “overcapacity” or dumping to grab market share we didn’t want to give up (in no small part because American taxpayers were subsidizing investments in those sectors).

Blocking the Nippon Steel bid is a better example for those who accused us of being too protectionist, and I’m sympathetic to that critique. But you can also read that as the President listening to and taking seriously the concerns of the Steelworkers Union (though there was dispute here between union management and rank-and-file).

But the bigger problem for both Group 1 and Group 3 is the politics. A lot of voters are warm to tariffs, and ever since Hillary turned on the TTP, forget about sweeping trade agreements (good riddance, imho—those docs were far too influenced by special interest carveouts).

Wi argues that “someone—anyone—needs to start making the full-throated, unapologetic case for trade as a source of American strength, not a political liability. Right now, the debate is entirely shaped by its opponents.”

A lot easier said than done. But it’s kinda what we were trying to do at CEA in the links at the end of my piece, especially the ERP chapters. And ftr, it wasn’t that easy for me to get there, coming up as I did during the EPI years in the 90’s and 00’s, warning about the China shock to mostly deaf ears.

I now agree that we should make the unapologetic case for robust trade flows, but we should a) be equally full-throated against unfair, distortionary trade when we see it, and b) not be silent about the people and places hurt by our persistent trade deficits. One of the things we tried to do—with considerable success if not much recognition—is steer investment (a lot of which came from abroad) in domestic manufacturing to those very people and places.

That’s the both/and, Group 3 way forward. It’s not the only way, but it’s one that makes sense to me.

I guess I’m in group 3, having been raised academically in group 1. With that said, I’m still not satisfied with the nexus between the economics and the politics of trade benefits. It seems to me that the real value of tariffs or other targeted NTBs isn’t to protect domestic industries - a long-term quixotic effort. Rather, we should use these measures to explicitly correct for externalities and other artificial inefficiencies. 10% tariff because our producers are hurting? Booo! 10% tariff to correct for lax labor and environmental standards? Yes! We shouldn’t just say free trade is good or bad when it is clearly good when the partner is on similar levels wrt its regulatory environment and political system and clearly bad when the partner is an authoritarian regime that is oppressing its own labor force and using subsidies to overproduce. I think this is the spirit of the Biden approach but it was not well articulated to the public, leading to most people thinking Trump had won the argument on trade, which of course was as much about HRC and Bernie pushing back against the Obama approach.

With respect, I think you have the political economy wrong here. It's not about making a case for trade agreements and people's general thoughts on tariffs it's about the cost of goods.

Everyone agrees that inflation was one of the 'top three' issues for voters. And by inflation, voters didn't mean the current rate of inflation but the post-pandemic cost of living increase. Cutting tariffs on China would have decreased costs on products and decreased the cost of living. Biden's promotion of domestic manufacturing (which includes the Chinese tariffs), whatever you think of it on the merits, did not give any political benefit to him.