Data_Note: The Data Are Confusing, But We Can Still Get A Decent Bead on Where We Are

Where we're headed...now that's a taller order.

One of my mantras is: “Hey, it’s data! It’s often going to be confusing!”

This is a very good time to chant this truism. The soft data—opinion/vibe surveys—have generally been quite negative, as you’d expect given Trumpian chaos, which this week added the existentially terrifying dimension of setting the military on lawful protesters and assaulting and handcuffing a senator who spoke up at a press conference. That said, preliminary data from the UMich sentiment survey for June popped up sharply, meaning even the vibes data are jumping around.

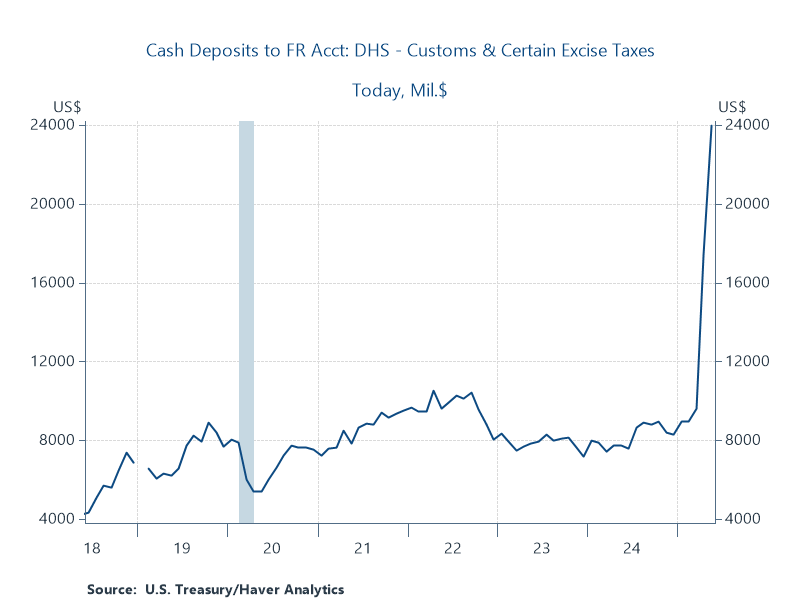

There’s clear evidence from hard data that tariffs have impacted firm behavior, generating extensive front-running efforts to stock-up inventories ahead of higher tariff rates, as well as an historically huge spike in tariff revenues, showing U.S. importers are facing a tripled tax bill on their imports.

And yet May inflation mostly came in as soft and mild as a May afternoon, slightly below expectations as I showed in my CPI-day post. The PPI—wholesale prices—was similarly subdued. Meanwhile, continuing UI claims (the stock of workers getting claims vs. the flow of initial claims) keeps nudging upwards.

What, in the name of Keynes, is going on?!

Here are some theories about inflation, each followed by my assessment:

—Just you wait, it’s coming. Importers built up inventories to front-run the tariffs; firms took advantage of “sellers inflation” (exploiting the shock to raise prices more than costs) to boost margins during the pandemic, giving them a buffer to maintain prices now, even as their costs rise. But these strategies can only stave off price effects for so long.

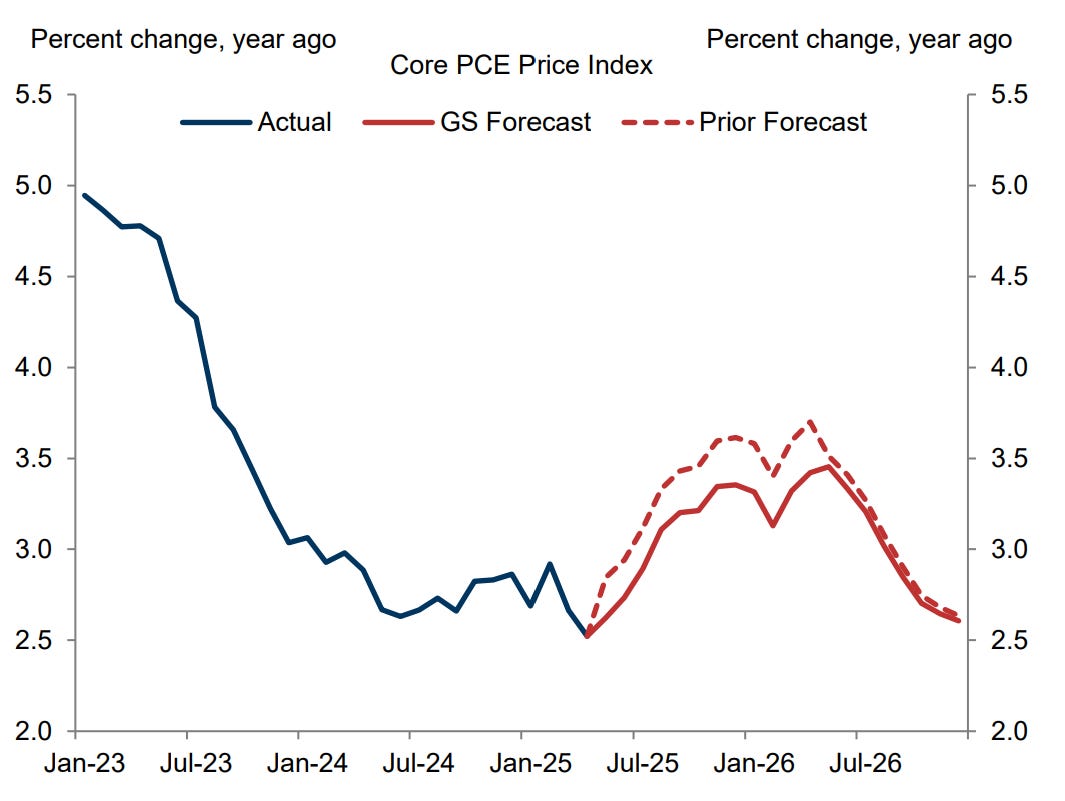

JB says: This one is most plausible, but seeing is believing and while the historical evidence clearly supports much more passthrough than we’ve seen, we’re in ahistorical waters. It’s notable that GS researchers still see a price bump coming, but have shaved their estimate down some.

Source: Goldman Sachs Research

—It’s there; you just have to know where to look for it. The average monthly price change for major appliances, 2023-24, was -0.6%. In May, that price jumped 4.3%, and its average since Feb ‘25 has been 1.3%. Toys averaged -0.3% in ‘23/’24 but popped up 1.3% in May and have averaged 0.1% since Feb.

JB says: Meh. I just cherry-picked the categories of goods with high import propensities that followed this pattern. There are a bunch of others, like apparel and new cars that go the other way. And the monthly numbers for these components are highly jumpy.

—Exporters are eating the tariffs. This is, of course, the White House line. The Customs revenue figures suggest otherwise, though without a counterfactual, it’s hard to say how much exporters are passing forward to importers (exporters could be holding down prices and we’d still expect a revenue spike).

JB Says: Strongly doubt it.

—Sellers, fearing the elevated price elasticity of demand, are resisting price hikes. Consumers are nervous about where things are headed, perhaps amplified by some labor-market softening I document below, so they’ll react highly negatively to any price bumps. Retailers get this and are holding back on pass-through…for now. Note that this is the opposite of how this worked during the pandemic, when consumer demand was quite UNresponsive to price increases.

JB Says: I suspect this one is in play too, but like the “just wait” story, it can only hold for so long.

—Constrained supply is being met with reduced demand. The idea here is that tariffs are pulling in the economy’s aggregate supply curve which, by itself, would raise the inflation rate. But at the same time, the aggregate demand curve is also moving in, leaving inflation unchanged.

JB Says: Plausible, but I haven’t seen enough evidence of either dynamic to lean very far into this one. Trade flows don’t seem much diminished (less from China, more from elsewhere), and neither does demand (though I have worried aloud about the relatively low 1.2% real increase in consumer spending in ‘25Q1).

One other point on inflation before I move to a brief comment on the job market. When I was at CEA, we kept expecting and hoping that shelter inflation would get the h-e-double-hockey-sticks back to it pre-pandemic trend. Our modelling predicted that would eventually occur, and recent data suggest this heavily-weighted series (35% weight) is closing in on its pre-pan trend. The figure below shows its 3-month annual rate in May was 3.3%, the same as its 2018-19 average (but see ftnt).1

Two signs of weakness in the job market

The figure below registered a “big yikes” from Guy Berger. It’s continuing UI claims which have been edging up for awhile, even as initial claims have been pretty chill. This is fully consistent with a labor market that does not yet have a layoff problem but does have a hiring problem. Which in turn, seems to me totally consistent with the wait-and-see curse that the Trump trade war has cast on businesses, consumers, investors, and the Federal Reserve.

Okay, then why hasn’t the unemployment rate gone up? Greg Ip points out that it has—if you go out to two decimal points:

The labor market today isn’t tight; it’s showing cracks. The unemployment rate, to two decimal places, has risen every month since January, by a quarter percentage point in all. At that pace it would reach 4.6% in the fourth quarter. This suggests the economy is growing slightly below its potential, which should keep a lid on price and wage pressures.

I’d call “meh” on that one too. Such small changes in the survey from which these data are drawn are statistical noise. But it is true that the jobless rate has climbed from the mid-3’s to the low 4’s since early 2023. I’d call that going from really full employment to less full employment. The main question is whether employers are generating enough jobs, given labor force growth, to keep the unemployment rate in the relatively nice neighborhood in which it has long been. And the answer to that, for now, is yes.

There is, however, the pattern below, which tracks the raw numbers of the unemployed as well as the labor force. That last arrow is pointing the wrong way (labor force growth has picked up a bit, keeping the jobless rate from growing faster). Along with the continuing claims, this underscores the point that the direction of travel may well be towards more slack.

What does it all mean?

Greg takes this all to an interesting place: If inflation is cooler than expected (and see UMich note below), and the job market is weaker than expected, the Fed has room to cut. That’s solid Ipian logic, but my priors, and I’m far from alone on this (see GS figure above), is, as noted, inflation may be poised to pop (even if it is a one-time, tariff-induced jump that the Fed would possibly “look through”). And sure, the job market may be showing some cracks, but job creation is well ahead of breakeven and real wages have been up around 1.5% yr/yr, enough to handily continue to support consumer spending.

In other words, we’re still driving through the fog and therefore need more data about our surroundings to have a better sense of where we’re headed.

And let’s keep it real here. There’s a monster out there in fog who thinks he’s the king, and that makes the path forward a lot more treacherous.

[This just in: UMich sentiment pops up bigly in preliminary June report, and inflation expectations also fell sharply. “Consumers appear to have settled somewhat from the shock of the extremely high tariffs announced in April and the policy volatility seen in the weeks that followed.”]

Using the full shelter categories, which includes hotels and some other adjacent categories, flatters this comparison. If you do this with just rentals and homes, the current growth rate is still about half a ppt above the pre-pan average.

I've been a little worried that democrats are fighting the last battle. Sure MAGA was able to weaponize the pandemic spike in inflation against democrats to win in 24 election. But my opinion is that if not inflation MAGA would have just found something else to club democrats with (trans). At least MAGA waited until after the pandemic inflation spike to pounce. Democrats, as Trump took office decided to make the argument that Donald Trump won the election by promising to lower prices on day one and tariffs will bring inflation. Tariffs may bring inflation but could it also not result in a global slow down. Tariffs raise prices on imports and in many cases these imports have no domestic suppliers or serve as necessary components for domestic manufacturers. This raises prices if demand stays steady. But consumers could just decide not to buy the more expensive stuff, (Donny 2 dolls). In that case slow growth and job loss has begger impact than inflation.

Bernstein's analysis is great about the numbers except for one guesstimate number he left out. We likely will see over a million or more undocumented workers leave the U.S. this year. Loss of undocumented workers and their families will likely increase inflation, lower GDP, and likely improve wage growth. But will it increase or decrease measured unemployment? Thoughts Dr. Bernstein?